Light Cameras

PROFILE-May 2010

Photographs by Brenton Hamilton

The Maine Media Workshops is a photographic mecca in Rockport. Peter A. Smith spoke with the workshop’s founder, its teachers, and some of its worldly disciples.

1

In 1972, David Lyman attended a ten-day workshop at the Center of the Eye in Aspen with Bob Gilka, National Geographic’s director of photography. When he showed Gilka his portfolio, Gilka’s reaction was, “Do you earn a living with this stuff?”

His dream—the dream for so many aspiring photographers—of working with the magazine was shattered, at least temporarily. The following year, during a trip to Camden, Lyman

stumbled on the snowy ghost town of Rockport. He rented out space beneath the old town hall and transformed the basement of Union Hall into a classroom, office, and a film-processing lab. The next summer, in 1973, hundreds of students and teachers, including three photographers from National Geographic, came to teach at the first Maine Photographic Workshop—an early testament to the enduring magnetism of Maine.

The Workshops attracted Ernst Haas, a father of color photography and a Magnum photographer whose ashes are buried in Camden. The late Arnold Newman. When motion-picture-artist workshops were introduced in the early 1970s, Vilmos Zsigmond, who shot Deer Hunter, came. Ralph Rosenblum, the director of photography for Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, László Kovács, who photographed Easy Rider, and Garrett Brown, the inventor of the Steadicam, all taught at the Workshops. Appalachian documentary photographer Shelby Lee Adams came. So did Sally Mann, Paul Caponigro, Mary Ellen Mark, Amy Arbus, and Eugene Richards.

This year’s course catalog is still a who’s who of contemporary image-makers.

2

Each summer, photographers come and go, taking hundreds, if not thousands, of photos from the Goose River Bridge in Rockport—so many that the bridge is supposedly scarred from the positioning and repositioning of tripods. The legacy of the Workshops does not hinge merely on taking photographs of something. And these photographs of the harbor collectively hint at the bigger picture: what the place is about—a coastal mecca attracting photographic pilgrims who scour the world for lightness, darkness, and life-changing epiphanies.

“It’s Biblical. Mat beget Pat and Pat beget whomever. Maine beget most of the other photo workshops. It was the first,” says Sean Kernan, a photographer who teaches at the Workshops. “It’s still finding its way and that’s what is appealing about it. It’s more

experimental, more artsy and probing. Something yeasty happens. For example, this guy Duane Michaels, who’s a secret master of photography with a deep, kind of crazy Tibetan wisdom, comes out of his cave every five years to teach a class. He has an effect on

his students. He rips their heads off and puts them back on backwards. They walk out with a different perspective. He really takes people beyond the question of ‘What is photography?’ to question, ‘What is the universe?’”

The place is like a religious summer camp for artists who believe in magic. True believers describe the intense immersion in the summer program as a mystical, magical, and transformative experience. Russell Carpenter, a Los Angeles cinematographer, the director of photography for the film Titanic and teacher of a Master Class, says, “You’re taking a break from civilian life, going up to this beautiful coastal town, and that’s where the chemistry happens. As much as it sounds like woo-woo, I’ve seen the magic.”

3

Barbara Goodbody raised three children in Cumberland, and as a 50th birthday present to herself, she enrolled in a two-week workshop in basic photography with Craig Stevens in 1986. “I was absolutely terrified. I didn’t have much self-confidence,” she says. “I’d always loved Life and National Geographic and I decided that photography might be a good thing for me to try. I’d heard of the Workshops. But, until then, I had never entered the world of image making and encountered such creative people.”

Years went by. Others came and found the magnetism inescapable—Cig Harvey, Jonathan Laurence, David Wright, and Shoshanna White. Others, like Jon Edwards and Samantha Appleton, lived in Maine and came to the Workshops to refine their eye. Goodbody continued shooting and now has work in the permanent collections at the Portland Museum of Art and the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

The Workshops expanded to include filmmaking, and to offer associates degrees and professional certificates through what was known as Rockport College (in partnership with the University of Maine at Augusta). For a short time in the early nineties, Kodak opened the rival Center for Creative Imaging, which arrived in the area because of the Workshops and focused on digital imaging in the era of a 1-megapixel camera. The center ultimately fell apart and was sold. Meanwhile, the Workshops persevered. Barely.

4

By 2004, the institution was on shaky financial ground. The Camden National Bank filed a foreclosure notice on its mortgaged properties. The New York–based holding company Leucadia National Corporation (a sort of mini Berkshire Hathaway) then acquired the bank notes. In the winter of 2007, Lyman, in order to avoid bankruptcy, turned the workshops and the college over to the nonprofit Maine Media Workshops. Leucadia then donated a portion of the current campus on Camden Street.

Lyman took off to sail the world. And a nonprofit organization—informally known as the Rockport Six—took the helm of the workshops. The initial board included photographers Charles Altschul, Joyce Tenneson, and Goodbody, along with Joan Welsh, now a state legislator representing Camden/Rockport, Peter Ralston of the Island Institute, and John Claussen, an environmental lawyer who lives in Camden.

“Each of us had different reasons,” Claussen says. “I saw an institution that was of value to the local community, bringing in several million dollars, and the film and photo community outside the midcoast. Its absence would have been felt. That’s for sure. As someone with business and legal background, they told me they really needed me—and I reacted.” Claussen is still the board chair.

Tenneson and Goodbody had been inspired—or transformed—by their experiences. “I want this place to persevere,” Goodbody says. “I was gifted with that experience and I want to help others to have the experience for themselves.” She remains a board member, an active fundraiser, and of course, an attendee of summer lectures. “To be able to go to those and sit there in blue jeans and feel like a colleague of these enormously successful people. That’s where the magic is.”

5

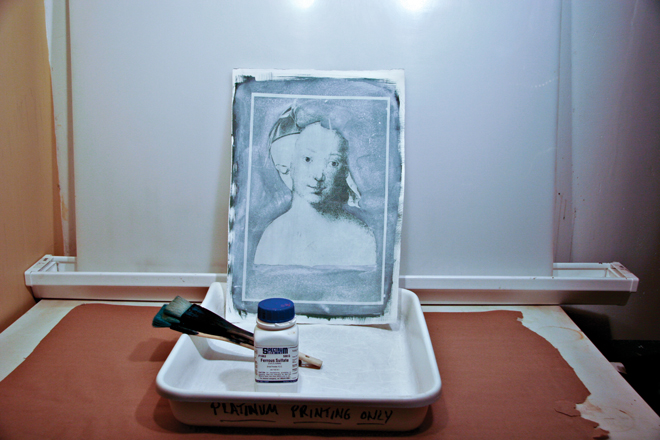

Brenton Hamilton, a resident teacher, scholar of historic photographic processes, stands at the head of the classroom earlier this spring, looking over student photography from his Projects and Portfolio class. The tension in the classroom is as thick as the fog wrapping Indian Island Light on a summer morning. The students have all been shooting for ten weeks, and the next ten weeks appear very uncertain—trips to Lewiston, trips to Portland, trips that explore who they are and what they’re doing with cameras. Most student don’t seem to know exactly where they’re going, what greater light they’ll find. But Hamilton reassures the class that he is willing and wants to be a mentor. “I’m like a guide,” he says. “I’m making sure there’s no water in your canoe.”

If there’s dogma at the institution, it is not apparent. Teachers and students talk about the reciprocity—the inspiration that students get from teachers and teachers get from students. Thatcher Cook, a Mainer who longed to take classes at the Workshops as a kid, would pore over the course catalogs in the back of his parents’ car (just for the photographs, mind you, there were no articles). He eventually took a summer workshop and landed a coveted position as a teaching assistant. Cook returned to the workshops to teach and to lead the Darjeeling Tea Plantation Workshop and the Spain and Morocco Workshop overseas.

Cook’s photographs often depict the work of international nongovernmental aid organizations—how the Mercy Corps helps women in Sri Lanka, for example—but he says something has surpassed his own work: the work of his students, two of whom started multi-thousand-dollar NGOs. “And, you know,” he told me, “that makes a bigger impact on humanity than a lot of the field work I do.”

6

The alternative processes lab is down by the parking lot, where you’re apt to see bright blue cyanotypes laid out on the lawn or hanging to dry on a clothesline. There’s a library full of film scripts in the Haas building and a fully functioning sound stage. Under the cafeteria are black-and-white darkrooms. Rolls and rolls of metal spools pile up next to the source of a smell that, for anyone who knows what D76, stop bath, and fixer are, conjures up a photographic craft that means safe lights and wet chemistry.

“There is a real dedication here, that I share, of respecting and promoting the historic processes,” Charles Altschul, a photographer and graphic designer instrumental in early Adobe programs who is now Maine Media Workshops president, says. “Whereas at the same time, there’s a great interest in existing at the cutting edge. I love the letterpress and handmade paper, but I’m also up on the latest digital techniques—whether that’s high dynamic range photography or 3D cinematography.”

Two floors up from the darkroom, there are dozens of Macintosh computers, a media laboratory, and a rental place with brand-new Canon Mark II digital cameras that can shoot high-definition digital video. Tim McLaughlin, who worked with multimedia pioneer Brian Storm in New York before being hired as the Workshops’ multimedia director says, “I think we’re pushing photography forward in terms of the future of media and the future of journalism. There’s a willingness here to be flexible.”

7

The Maine Media College, the year-round adaptation of the Workshops, is authorized to give masters of fine art degrees by the State of Maine and is currently seeking national accreditation. “The school’s reputation is in the Workshops,” Altschul says. “We have 20 times, no, 200 times, more summer workshop students than we have winter college students. We think that going through the accreditation those proportions will change. We expect the college to grow significantly.”

In the seventies, Rockporters once dubbed photographers taking summer workshops “Blue Dots” after the Sylvania flashbulbs they used. Used once, the blue dot on the disposable flashbulbs faded. The institution sometimes had a reputation for attracting students that, similarly, burned bright in the summer, then disappeared. A Blue Dot was a subset of the typical tourist. Maine Media Workshops has attempted to branch out, expanding into the community—with YoPhos (Young Photographers) and YoFis (Young Filmmamkers), scholarships, and public events.

As much as the school instills technical skills—how to select an f-stop, how to change the ISO on a digital camera, or how to make high-end color corrections in Adobe After Affects—everyone I talked with told me the place is not

focused on the brand-new 21 megapixel cameras that Canon loans them each year or the new iPhone photography class. Those are a draw, but it’s also about the history and the legacy of the craft—the generations of photographers hanging their work down at Union Hall, the generations bound inside the books at Tim Whelan’s bookstore on Main Street, those who have come through and continue to come through—all of them attempting to capture something real with silver emulsion, to transfer images onto 21 million pixels of red, green, and blue, to chase life with film that flickers by at 24 frames per second. All in an attempt to transcend the technological limit-ations of light-capturing devices and move the world from lower to higher intensity. There’s no doubt the Workshops leave its mark and not just on the decking of Goose Rivers Bridge.