People of the Lake

FEATURE-August 2013

By Jaed Coffin Photographs by Fred Field

The residents of Greenville and the unknowable future of Moosehead

On an unseasonably hot Friday morning in May, Heidi St. Jean, her eyes hidden behind black Dolce and Gabbana sunglasses, wanders around a yard sale on Moosehead Lake Road while waving her hand at a cloud of black flies swarming around her face. A native of Greenville, St. Jean is taking a break from planning the Indian Hill Trading Post’s thirty-fifth anniversary celebration on Saturday. After losing her job two years ago as the editor of the now defunct Moosehead Messenger newspaper, St. Jean took a job working the register at Indian Hill, a position she held as a teenager when her father managed the deli over two decades ago. In recent years, Indian Hill Trading Post has expanded from a small grocery and general store to a mini-mall of some 35,000 square feet, offering merchandise from Ugg boots and ketchup to rifles, canoes, and ice augers. Because Heidi is internet-savvy, she suggested to the owner that he hire her as Indian Hill’s new online marketing director. Now, the shopping center has a Facebook page and a twitter feed—a rare buffet of online presence in a town that, until just recently, only had access to dial-up internet service.

St. Jean, now chatting with the yard sale’s proprietor whose face is invisible behind a bug veil, has lived all of her 47 years in Greenville. Having endured two divorces, single motherhood, and “agoraphobia/panic disorder,” she is the creator of a blog called Life Warriors, which aims to “uplift women with inspirational stories.” Her worldview was changed, she says, by a group of spiritual people from California, but it also reflects the spirit of her 1,700-person hometown. “The community here is amazing,” St. Jean says. “Something happens to someone, and people organize a benefit within five minutes. We just take care of each other.”

Then Heidi tells me the story of her daughter, Emily Patrick, the valedictorian of her 19-person class at Greenville High who recently graduated from the University of Maine with a degree in wildlife ecology, earning the highest GPA of any student in the university’s college of forest resources. The mother of a one-year-old daughter, Patrick is spending her final summer in Greenville. In the fall, she’s headed to Southern Oregon University, to pursue a master’s degree in environmental education.

As St. Jean’s parents, former employees of the local but now defunct Scott Paper mill, wander through old pairs of skis and combat boots, 80s era winter jackets and vintage barber stools, St. Jean gazes north toward the hundreds of thousands of acres of wilderness that surround Maine’s largest lake, and concedes that the departure of talented young people like her daughter from Greenville “just might be inevitable.” Then she gives me her phone number, and says that if I have any more questions about her hometown—of which she seems to be an unofficial ambassador—that she and her daughter would be happy to meet up tonight at a bar called the Stress Free Moose.

Driving into downtown Greenville is not like driving into the small towns in southern or coastal Maine: there is no strip of fast- food joints and chain drug stores preceding a quaint and thriving downtown business district. From the Indian Hill shopping center, you can see only a narrow view of Moosehead Lake: an expanse of blue dappled with islands and nestled into layers of gentle mountain ranges. At the bottom of Indian Hill are outfitters advertising moose safaris and rafting trips and fishing guide services. Most of the parked vehicles in town are trucks. At the intersection of Pritham Avenue and Moosehead Road is a small collection of bars and restaurants, a souvenir trading post, a church, and a soft-serve dairy bar. Floating in the waters of Moosehead Lake is an old white steamship called Katahdin, which will celebrate its hundredth birthday later this year.

From the mid-nineteenth century through the first three decades of the twentieth, Greenville was a jumping-off point for wealthy tourists who rode trains from Boston and New York and Philadelphia into the wilds of Maine, then boarded Katahdin and some 60 other steamships like her to travel to a series of resorts and cottages among the shores and islands of the lake. Following the Great Depression, the luxurious tourist economy of Greenville tanked; the grand resorts that once served the wealthy barons of America’s industrial revolution burned down or were left to rot. For the next forty-something years, the old vessels that once carried everything from livestock to building supplies underwent a transition in purpose: during the heyday of Maine’s lumber industry, the vessels hauled lumber booms of up to 60,000 tons from the north of the lake to the southern end, where they were then transported to mills in the south. But those days ended, too: in 1975, Katahdin—a steel-hulled steamship that, unlike her wooden fellows, did not sink or rot—hauled her last load. Since then, the most significant event in the town’s economic development was the recent acquisition of over 400,000 acres of wilderness by the Plum Creek development company in what was proposed to be the largest development plan in the history of the state. Despite the promise of nearly 1,000 housing lots, golf courses, hotels, marinas, and RV parks, the new construction still hasn’t begun. These days, just weeks from the start of another tourist season, the people of Greenville are waiting to see what’s next.

Jeff Johanneman, co-owner of the Greenville Inn with his wife, Terry, is manning the front desk on a quiet afternoon. Last night, most of his rooms were empty, but tonight brings promise: he’s got seven rooms reserved. As the inn’s sixth owner, Johanneman, from New Jersey, left behind his careers as a contractor, an airline pilot, and a flight instructor ten years ago to move into a home that once belonged to William Shaw, a famous nineteenth-century lumber baron. “I fell in love with the woodwork,” Johanneman says when explaining what made him and Terry move here. He shows me the ornately turned railing spindles, the various lines of mahogany trim, the rich and knotless paneling on the sliding doors, the six-foot-tall stained glass window adorned with a sprawling spruce tree—a symbol of the commodity that, ultimately, allowed William Shaw to buy such a mansion. After buying the inn, Johanneman and Terry did a lot of the remodeling work on their own. “To date,” Johanneman says, “we’ve used 51 gallons of paint.” Johanneman shows me Shaw’s old room, which looks out across an impressive view of the lake and the mountains beyond. In the basement, Johanneman says, “there used to be a nightclub, with bands that played all night.” Now? “It’s just an old basement. No reason to go down there.”

Typically, Johanneman finds that about half his guests come from Maine, while the other half come from all over the world, from Singapore to Germany. “It’s the lake,” Johanneman says. “They come here for the lake.” His most recent noteworthy guest left just a few days earlier. Gerry Adler, the 80-year-old survivor of a B-52 bomber test flight that crashed into a nearby mountain, recently came to the inn to celebrate a fiftieth reunion with Eugene Slabinski, the Greenville local who braved the frozen night to save Adler’s life. As a former pilot himself, Jeff Johanneman was honored to provide Adler with a place to rest while he spent time with Slabinski.

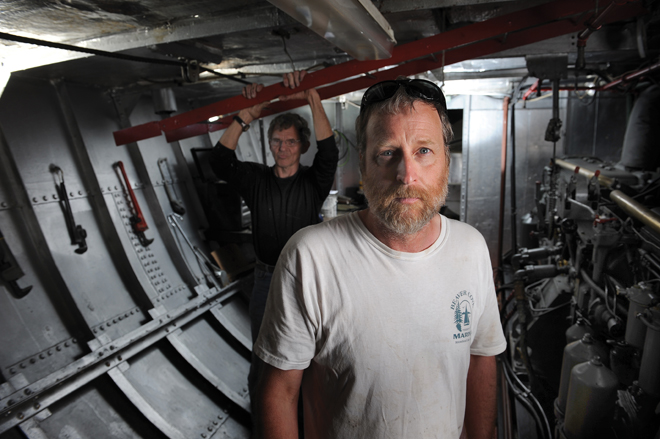

Shaded from the afternoon sun by the upper deck of Katahdin, Pete Noyes, Maynard Russell, and Jon Amtower break from a long day of repairs and renovations. Noyes takes me on a tour of Katahdin, a ship that arrived in Greenville by railroad in 1913 in three steel sections. As much as any human, Katahdin has witnessed Greenville’s evolution over the last century: on the bow of Katahdin is the number 63, signifying that it was the sixty-third vessel built by Bath Iron Works, the storied shipyard 150 miles south which has now produced nearly 500 vessels. The wood of Katahdin is old and dark and beautifully preserved; down below, the engine room has been freshly painted. In the last year, the ship received $430,000 in repairs, including a new layer of steel, via a $300,000 grant and donations, but to people like Noyes, the soul of the ship remains the same.

“She means a lot to this town,” Noyes tells me while standing in the engine room. Before taking a new job as an engineer on Katahdin’s crew, Noyes worked in “the woods”: as a “tree-scaler, woodcutter, skidder, machine operator.” Noyes declares himself “a graduate of University of Great Northern”—a reference to the paper company that owns land north of here—and chalks up his knowledge of so many useful skills to something he calls “OJT: on the job training.” Noyes has noticed the way his town has changed over the last decades since the end of Moosehead’s thriving timber industry. The future, he knows, depends largely on Greenville’s ability to draw in people from other parts of the state, and from across the country. He’s impressed by families and couples from Boston who come up every weekend, and understands the power of the lake in bringing them north. “It’s always the lake, the lake, the lake,” Noyes jokes. “Sometimes it makes me wonder how bad it must be where they come from.” But Noyes, a new grandfather whose daughter lives out of state, is concerned that this community is losing its own. “We tend to export everything,” he says, “including our children.” He raps his hand on the steel hull of Katahdin. “In some ways, I guess this ship resembles the character of our town. It’s always done what it has to do in order to survive.”

In the Moosehead Marine Museum, Sue Bair, the chef for Katahdin’s summer cruises, is answering phones at the desk. Today, there are no visitors; soon, she imagines, the crowds will come. Bair refers to the ship as “my yacht,” and Lady Kate. Her family goes way back in this town: her grandparents worked for Stover Plywood in the 70s; her great-grandfather, she says, is Louis Annance, a former chief of the unrecognized St. Francis Maliseet tribe of New Brunswick. After spending the last 30 years in Connecticut, Bair came back to Greenville to be closer to her family: her daughter works as a hairdresser in town, her son works for a barge company. “Years ago,” Bair recalls, “this was a unique town. The lake brought in the city folk. But we’re losing an important generation, and the special skills that are going to be long gone.” Bair takes me to a wall lined with old logging tools and spiked boots, a section of the museum where a photograph of William Gary, one arm balanced on the wheel of Katahdin during the final logging drive of 1975, gazes across scale models of old steamships, many of which remain on the bottom of the lake.” She recalls what it was like coming home after being away for so long: “It was sad,” she says. “My once-thriving little town still hadn’t grown. We used to have a lot of fun here.” As a girl, Bair remembers swimming in the lake in the early spring, just after “ice-out.” She also remembers daring her friends to run across the log booms, until the mill workers called her parents.

In Rockwood, there’s a restaurant called Maynard’s in Maine. It looks like a hunting cabin from the outside: the porch is built from old logs and the walls, inside and out, are decorated with dozens of pairs of antlers, and stuffed creatures big and small, local and exotic: there are tortoises, foxes, deer heads, leopard skins. The only way to eat at Maynard’s is by making a reservation. On the menu that night, by phone, I was offered two choices: steak, or haddock. In the dining room, there are half a dozen tables of guests, many of whom are staying in the nearby cabins. One of the groups calls itself the Jersey Boys. There are roughly ten of them here tonight, but three brothers, Bob, Jon, and George Engstrom, are here to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of their first trip to Moosehead Lake. They heard about the Greenville area at a sportsmen’s show in New York City in the 60s. Now, they come up here—“strictly the guys”—every year.

The steaks at Maynard’s are roughly the size of my head, plus my hand. A quick glance suggests that no one here is part of Maynard’s clean plate club. This is the portrait of Moosehead as it used to be, during a period of American postwar prosperity when the fish were plentiful and the steaks were huge and there was plenty of salmon for everyone.

Later that evening, I follow the Jersey Boys to a fly-fishing spot at the foot of a dam. As the sun sinks into the darkening tree line, the dozen old friends cast into the quick rapids, unspeaking, as if an L.L.Bean catalog, a Norman Rockwell painting, had suddenly come to life. On the road out, a small red fox darts out of the woods, runs along the gravel for several yards, pauses, then pops back into the forest as dusk fades to night.

By 8:30 p.m., downtown Pritham Street glows with activity. The tables of Flatlanders bar are full, and the dairy bar is bombarded by two teams of a regional fifth- and sixth-grade girls softball league. The porch of the Stress Free Moose is cheerful and crowded with tables of locals. Heidi St. Jean comes in with her daughter, Emily Patrick. Patrick isn’t in touch with any of her high school friends any more. “We’re losing people fast,” she says of her class, and remarks that many of the lower grades at Greenville High have classes in the “single digits.”

There are four generations of St. Jean women in Greenville tonight, including Heidi’s mother and Emily’s daughter. Sitting with them it’s hard not to consider how time can affect a small community that has undergone such vast industrial and economic changes as Greenville has. Patrick tells me that she’ll miss seeing her grandparents as she did when she grew up here, and laments that her daughter might not grow up around her mother. Her daughter’s childhood in Ashland, Oregon, won’t be like Patrick’s. “My grandparents raised me, they were like a second set of parents. Going to high school, everyone knew each other. We shared each other’s beer. It was safe.”

I ask St. Jean and Patrick what it would take to make it work in Greenville, such that an academic star like Patrick would ever consider staying here. St. Jean answers for both of them. “I don’t know what it’s gonna take to make this work,” she says. “More exposure. It’s got to be tourism. We’ll come back. I don’t know how. But I do think it’ll boom again.”

Before leaving, St. Jean hands me a bundle of old copies of the Moosehead Messenger. On the front of every paper is a story under the heading “Celebrating Olde Tyme Moosehead.” There are photos of Kineo boat races, the old YMCA that burned down in 1978, a logging sluice from the 1890s. By the look of the shiny white ribbon that St. Jean has tied around the papers, it’s clear that these are stories she is proud of.

That night, bright white lightning and thunder rip over Moosehead Lake. It rains powerfully, and for a moment I step onto the porch of my small cabin at the Greenville Inn to watch the sky. By morning, the rain has cleared. I jog through the empty, quiet streets of downtown, past two categories of houses. There are the vacation homes, with fresh paint and the sparkle of recently completed remodels; then there are the houses that look more locally entrenched: partially wrapped in Tyvek, porches half-rebuilt, additions started but, for the time being, on pause. To the unaccustomed, these are the marks of disrepair. But to me, this is the mark of resourceful people, who do things for themselves, who don’t pay for contractors to fix up their lives, but rely on their own OJT skills to work on their homes when their workday is over, when the weather allows for it, when the seasons give them time. These people, in my mind, are the people of the Lake.