Elaine G. McGillicuddy

WELLNESS-November 2013

By Sophie Nelson

Photographs by Patryce Bak

“the house of our Love” : the joyful remembrances of poet, yoga practitioner, and peacemaker Elaine G. McGillicuddy

When you lose someone but you love them with a love that allows for the losing they fade sadly, albeit beautifully, into time, appearing in a scent on some stranger’s wrist, or in a photograph from a forgotten shoebox, or at the start of spring, say, if they loved spring. Then there are those people in our lives whose leaving changes almost everything. And there are certain kinds of love that don’t take losing well. The love Elaine McGillicuddy shared with her late husband, Francis McGillicuddy, was a love like that. He died at the age of 82, in January 2010. Three and a half years after his death, sitting on the floor in a sunny room at the back of the bungalow they shared for almost 40 years, Elaine tells me that she and Francis were of course aware that separation of this kind would come. But it’s clear in listening to Elaine that there is really no preparing for what ends and begins with the death of someone you are so close to.

If I had met Elaine McGillicuddy 40 years ago, I would have introduced you to a young woman who had fallen in love with a priest, and just left the convent. Thirty years ago, I would have introduced you to an English teacher, a woman who, alongside her husband (a former priest) was on the front lines of the ongoing peace movement. Twenty years ago, I would most certainly have included co-founder and director of Portland Yoga Studio alongside her name and 10 years ago, she might have been a leader of the Dances of Universal Peace; five years later, the co-creator of a permaculture oasis in suburban Portland. She is still all of these things, of course—her life has been rich beyond measure—but because I meet her now, handling her widowhood with words, she seems to me first and foremost a writer, and it is perhaps through writing that she will come out of grief, or, rather, move more deeply and ever more benevolently into it.

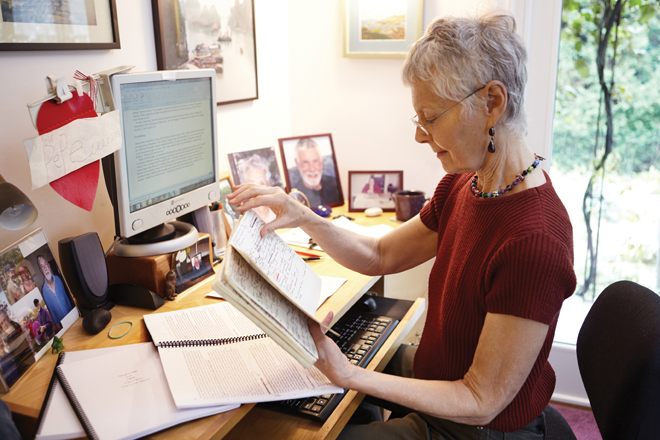

Upon arrival at her home I am enchanted by the permaculture gardens surrounding Elaine’s house, and especially by her way of being in them. At 78 she is lean and glowing, exuding strength, elegance, and vulnerability in her every movement while she introduces me to the many fruit trees (plum! sour cherry! peach!) around the periphery of her compact yard. Within that lush, gnarly rim are almost more plants than she can name in various stages of overgrown.As we walk along the narrow paths, she explains that she’s neglected the gardens while writing her book, but any hint of regret in her voice is overwhelmed by her wonder at how particular plants have fared in her absence. Inside her home, as in the garden, each item has a story—and there are so many memory-laden objects, so many photographs, so many books in so many stacks and on so many shelves, there is a lot to say. When it comes to memories, she’s got a collector’s itch, an inclination toward distraction. “How will you pull this all together?” she asks me with another photograph of Francis in her hands. His kindness radiates through the pictures, and I like to look at him, like to look at her look at him.

“This is how Father McGillicuddy looked when I first met him,” she tells me, pointing to a photograph of Francis in a frame on top of a piano beside a large wooden cross. He has strong, handsome features, wears glasses, a clerical collar, and dark hair in a thick swath across his forehead. He was 44 when they first met. She was 33. Although it was against the rules of their religious existence—the very same confines that offered opportunities for self-discovery and service, and also protected them from the domestic lives in little towns that, as teenagers, they weren’t ready to lead—they fell slowly and deeply and completely in love. Her love for Francis, along with exposure to a broader range of religious views in graduate school and the rampant anti-establishment sentiment of the 1960s, combined with other forces to cause Elaine to leave the convent. Francis had more difficulty leaving the priesthood. She calls their relationship from 1970 to 1972 the “underground period”: there were long phone calls and love letters, stealth meetings in motel rooms and in her studio apartment on Congress Street after they both moved to Portland. Finally there was a wedding, the bungalow in Deering purchased for $19,000.

They loved like they were lucky to be able to love, like a partnership had not always been within the realm of possibility, because it hadn’t. Sitting together on the floor, Elaine and I look through the letters Francis had written to her each year around Christmas, originally in keeping with the tradition of Marriage Encounter, a Catholic marriage renewal program they took part in. She tells me that they made a point of lying together, in each other’s arms, in silence or not, every day. She tells me about the conferences, retreats, and trips they went on, the personality tests they took, and the way Francis was an introvert. It’s clear that they had worked at knowing each other, not just as they were when they met but as they kept becoming themselves.

It was Francis who first introduced Elaine to yoga. She got a book out of the library—Yoga in 28 Days—and, before a month was up, became “addicted.” Her interest led her to study in San Francisco and as far away as India for nine weeks. In 1989, not far from the studio apartment in which she and Francis had conducted their clandestine meetups years earlier, Elaine and Francis co-founded the Portland Yoga Studio. That same year, the couple was awarded the Seeds of Peace Award from the Maine Peace Campaign, mainly for their work as conscientious war tax objectors. For Elaine, the peace work she’d been a part of since her 30s merged beautifully with yoga, which “takes people out of their reactive ways of living which lead to conflict.” On a yoga retreat at Fermes des Courmettes in Tourrettes-sur-Loup in the Maritime Alps, Francis and Elaine stumbled upon what looked to them like “an untidy garden,” and later set out to create such a permaculture eden of their own in Portland. The Dances of Universal Peace, also, came out of yoga. The Dances are circle dances that incorporate sacred phrases and chants from the various spiritual traditions and Elaine, although skeptical at first, came to love them in her 60s and 70s. Home from her first weeklong Aramaic prayer dance retreat in 1995, Elaine sang the songs around the house. Francis took to them too, and together they chanted the Lord’s Prayer and Jesus’ Beatitudes in Aramaic (the language Jesus spoke) at several national conferences. These and a particular chant from Song of Songs 8:6—“Set me as a seal upon your heart for love is as strong as death”—were the soundtrack of their later years together.

What appeared as pain in his back in 2008 eventually became intolerable and was finally diagnosed as a symptom of an unknown cancer at this time of year, four years ago. The last 100 days were bittersweet. There were moments of soul-shaking joy and knife-sharp sorrow. There was pain and there were people who relieved it. Since cancer had “chained him to his bed,” Elaine did everything for him in the weeks preceding his death. In a letter to friends and family, Elaine wrote, “Can you imagine what Francis said to me in his state of complete dependence? He said: ‘This is another wonderful moment, going through with you the little chores of getting me ready for bed. My beloved is here with me. She is preparing me. You look good, you feel good, and you are so good to me.’” Knowing from his past work as a hospital chaplain that the sense of hearing is the last sense to go, Francis asked that Elaine sing to him when he was dying. And so he was gone with the “love is as strong as death” chant ringing in his ears.

You could say Francis is still ringing Elaine, and that the bell tolls stories and poems. Elaine clearly thrives on the life she leads, and has found comfort tucking into it over the past few years while she writes her books. Because she has no children, she calls “peace work, yoga, the Dances of Universal Peace, and permaculture” her “offspring” and bequeaths them especially to Rowan, her spritely and much beloved nine-year-old goddaughter. She meditates and still does yoga daily—some advanced poses, even—to relieve a lifelong pain in her hip and probably some pains elsewhere.

She collected memories in the process of writing a book of poetry, Sing to Me and I Will Hear You – The Poems, and a memoir, Sing to Me and I Will Hear You – The Love Story, gifting them to “people who love love,” she writes, seemingly without realizing what a bold thing it is to share. Does she not know we’re expected to relate according to what’s wrong? That some of us are not sure what to do with a love like hers? Her unawareness moves me; it sounds like a naïveté that comes from wisdom we could use some more of, just as we could use more of Elaine’s kind of love—hard-won, and worked on, and turned inward and outward in extraordinary excess.