Lives on Call

FEATURE-January 2014

by Sophie Nelson

Photographs by Fred Field

3 Maine physicians trading perfection for excellence + embracing the positive in a pressure-filled profession

If you are not sick and no one you know is very sick and it is a sunny afternoon in Portland, it can be pleasant to wait for a doctor in the entranceway of the venerable Maine Medical Center. I recently waited on a bench by the coffee cart, before the stories-tall windows full of sky. I watched people come and go through the glass doorways and listened to the sounds of the piano being played in the corner, the murmurs of doctors and nurses in scrubs unpacking and eating their lunches in the long pools of light. But above me, expanding upward in those castle-like silos you can sometimes see from quite a distance, were so many people and so many health-care professionals trying to deal with so much illness. As that picture came into focus for me, so did the pressures—the weight resting on the shoulders of those salad-and-sandwich-eating, white-coat wearing mothers and fathers and daughters and sons—placed on the doctors all around me.

The challenges of working within the healthcare system affect not only providers but patients. Modern medicine is unspooling in miraculous and sometimes trying ways, and while we all contend with the intersection of medicine and technology and insurance companies and politics and pharmaceuticals, when it comes to the day-to-day work of physicians we’re talking life and death. We’re talking healing. Healers is a word doctors don’t often use to describe doctors. It is a word that Dr. George “Joe” Dreher uses—to my surprise—after we find a more or less quiet place to sit and talk in a booth-lined hall around the corner from the entranceway. I don’t know why it startles me to hear Dr. Dreher dip into the wellness vernacular. There is something classic about him, even traditional, that at first glance might seem in opposition to trendy health-speak but in reality shows the inherent relevance of such words and connotations. “Mindfulness” is another word he uses early on in our conversation, albeit cautiously: “It’s so popular now I worry about it being misused, sort of becoming McMindfulness. It might be easier to say resilience.” Whatever you call it, the now-retired physician began practicing it about 20 years ago, and he defines it as “being attentive to what’s going on around you, particularly within you, without judgment.” Tuning into the present moment, we avoid what is termed “monkey mind”: that state in which our minds run wild, making reality out of misinterpretation and assumption, distracting one from one’s physical self and physical surroundings.

This tendency toward hyperbole goes on in all of us, in any professional setting, but the consequences for doctors can be quite dire. Over the past several years a growing number of physicians have been leaving clinical medicine to do something else with their unique set of skills, and this burnout—sometimes called a “silent exodus”—is only expected to increase with added demands.

Knowing what a habit of mindfulness brought to his own life and career, and knowing what it might do to reverse any trend toward burnout at Maine Medical Center, Dr. Dreher began attending conferences focused on physician health and mindfulness in medical practice. In the fall of 2010, he started offering a Mindful Practice of Medicine course consisting of a dozen hour-and-a-half-long sessions; he and his team have conducted the course two or three times a year since, always with more people wanting to take the course than they had room for.

With the support of the president of medical staff, Jamie Zeitlin, MD, and others, he recently helped create a medical staff subcommittee on provider health and resilience. While he maintains these footholds at Maine Medical Center, Dr. Dreher recently retired after practicing medicine for 35 years. It was family practice—in particular the concept of treating the whole person—that originally appealed to him, and so after medical school and a residency in family medicine in Bangor, he helped to set up a practice in Dexter, Maine. As is the case for most family physicians, Dreher encountered many patients battling addictions and other mental health issues. He gradually shifted his focus, and later went on to work in an addiction center at St. Mary’s Health System in Lewiston and obtained additional training in psychiatry. He then decided to undertake the entire psychiatric residency program at Maine Medical Center, although he eventually gravitated back toward family medicine as a residency faculty member teaching the provision of mental health care within primary care. This fluidity among disciplines illustrates Dr. Dreher’s understanding of the inextricable links between mental, emotional, and physical health, and his desire to approach health and healing holistically—not just in the treatment of patients but in the interest of his colleagues as well. And Maine Medical Center and other health care professionals within that system are catching on. I am surprised to learn of the center’s meditation room, and of yoga classes and other emerging mindfulness courses taught and attended by doctors and nurses, administrators and other members of the health-care team.

“All of the things I’m saying have a lot of qualifications,” says Dr. Dreher, “But it’s easy in medical training to feel like you have to be perfect which is a very rigid, brittle way to be. An equally good and much more flexible way to be is working toward excellence. You can be a little more relaxed about yourself. Take your work seriously, but don’t take yourself too seriously.”

A week or so later, in the impressive, industrious, mini city of Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor, I sit on a couch across from Dr. Joan Pellegrini. She’s candid, commanding, and also a little silly—cutting through the hospital buzz with a marvelous choppy laugh as she tells me about why she started running. “In high school I was always an athlete, but never really a runner. That was something I started at 16, but it was more of a get-me-out-of-the-house-and-stop-fighting-with-my-mother kind of thing.” Anyway, the habit stuck: “I run so that I can eat chocolate, and I eat chocolate so that I can deal with my life,” she says.

But Dr. Pellegrini doesn’t just run—she runs marathons. And is a trauma surgeon. And mother to three daughters. Chocolate and joking aside, each of those tasks seems overwhelming in and of itself, and yet, from the sound of it, the exercise makes it all more manageable—a kind of mindfulness in motion. In the winter, when darkness and snow and ice make running nearly impossible, she straps on a headlight and skis along the railroad tracks behind her house. “I like marathons, but I’m not one of those people who runs for hours every day. Forty, forty-five minutes,” she clarifies. “There simply isn’t time for more than that.” But in a profession where a single bad outcome can be devastating, where exceptional mental agility and emotional stability are a given, the work one can do to take care of themselves is a gift to all of us. “A lot of times you have to look closely at yourself. You have to get up and wipe the dust off and say ‘I’m never doing that again.’” A bad outcome, however rare, weighs tremendously on a physician. “Sometimes, you have to remind yourself why you went to medical school—how fun it is to save lives and make people’s lives better.” Sometimes, a patient will remind her: “Maybe it’s because I’m little and I just give off that vibe. I don’t know,” she says, laughing that marvelous laugh, “but they hug me and they kiss me. It’s incredible.”

Well before she was Dr. Pellegrini, Joan was a girl from Anchorage, Alaska who loved to play the violin and Alpine ski. At Cornell University, where she joined the pre-med track, Dr. Pellegrini told herself surgery was out of the question. Her father was a thoracic and vorasic surgeon and was rarely home. Once at Tufts Medical School, she arranged her schedule so that surgery was her last rotation in medical school; as it happened, she loved it. “The creativity of figuring out how to put tissues together really appealed to me, which makes sense because I had this sort of artistic component.” To her independent-minded Alaskan surprise, she also liked the teamwork involved, and the scope: her interests are clearly broad, so it makes sense that she went into such a dynamic specialty.

She’s quick to credit her husband, an attorney in the Bangor area, for his help in making her career possible. She is also grateful to the family’s nanny, who has been a part of her childrens’ lives from the beginning, when she was juggling medical school and motherhood on a dime. “When I was in my residency, I basically just signed my entire paycheck and gave it to her,” says Dr. Pellegrini. “If she could take really good care of my children, that was the important thing. Otherwise, why am I doing any of this?” Her trust in this extraordinary woman makes it possible for her to be entirely present at work: “When you’re in surgery your mind simply can’t be anywhere else.”

Throughout our conversation, Dr. Pellegrini makes vague references to a time when she was seriously sick. It’s only after following through with a chronological recap of her life that she elaborates on this story at the center of it. As a student at Cornell, she experienced terrible stomach and digestion issues that doctor after doctor chalked up to psychosomatic symptoms of stress. After four years of debilitating discomfort and pain, the newlywed showed up to medical school jaundiced. The school nurse recommended a doctor in Boston’s Chinatown who recognized what was going on: ameba is an international traveling diarrheal illness that, when left untreated, can do serious damage. Over the next several years, Dr. Pellegrini was treated for the amebic infection, was diagnosed with colitis, endured bowel obstructions, and had many run-ins with doctors as a patient. Eventually she came through it, and is probably a better physician for it. “The reason I say it’s helpful is because I tend to attract female patients with chronic abdominal pain. And I think it’s sort of because I understand where they’re coming from. I can say, ‘I know how you feel, I’m going to do everything I can to help you feel better.’ You actually truly have compassion if compassion means to feel their pain.”

It was the promise of sustained, human-to-human interactions that drew Dr. Dana Goldsmith into pediatrics—the natural incorporation of preventative approaches to health. Helping kids stay healthy or feel better year after year remains his chief motivation. He reveals all of this to me in what he says, but, more importantly in what he’s done.

Childhood obesity has nearly quadrupled in the past 30 years and now affects about a third of children in the U.S. As this troubling trend became apparent in his midcoast practice, frustrated that he could only scratch the surface on his own, Dr. Goldsmith determined to assemble a team of fellow Pen Bay Healthcare providers and therapists to address the chronic disease. The Zing! program is now just over three years old, and has affected the lives of over 40 children and adolescents. “Trying to find the time to deal with obesity and overweight issues effectively [in a traditional clinical setting] is extremely difficult,” says Dr. Goldsmith. “I think we were missing the boat. It was all a guilt trip. Now we’ve flipped that around to say you have a chronic illness, and we can support you to help you get better.

While the collaborators—a nurse care coordinator with expertise in exercise physiology, registered dietitians, and mental and behavioral health specialists—each had a great deal of experience in his or her own field, they became trained in special techniques for talking to children and engaging with them in a way that would be supportive, non-threatening, non-biased, and non-judgmental. “We realized that we couldn’t address the obesity issue by itself until we addressed a whole other host of medical and behavioral health issues at the same time,” says Dr. Goldsmith. They also made sure to give Zing! participants their due autonomy: “We’d ask them, ‘How ready are you to do this, on a scale of one to ten?’” In the best outcomes, after the standard six-month period, Dr. Goldsmith and his colleagues have helped patients lose weight and/or stabilize their body mass index. These small but radically significant changes in the lives of young people Dr. Goldsmith cares so much about make the extra work worth it.

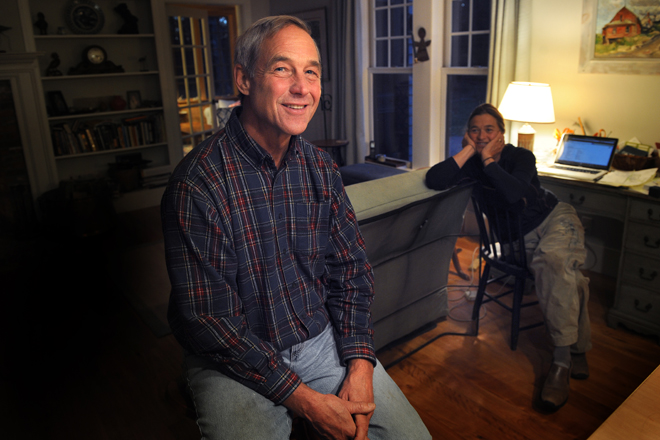

When I ask him how he stays healthy, he laughs a deflective laugh and mumbles something about his wife. But there’s a story there. And it’s a good one.

“One day about 15 years ago, my neighbor came by and asked me if I wanted to go for a bike ride.” He had the best excuse: no bike. But then of course his friend had an extra one he could borrow. Mile by mile, hill by hill, Dr. Goldsmith became a regular biker, bundling up on freezing cold days to get in his miles.

I like that this story so wonderfully mimics the supportive, incremental approach Zing! takes towards health. And the metaphorical miles and hills that physicians and their colleagues surmount to care for themselves so that they can care for all of us.

Dr. Goldsmith’s office is fairly small, at the back of a pediatrician’s office outfitted in elementary decor—cork boards covered in cartoons recommending tasty, healthy snacks. A map of area walks and water fountains at knee-height. Photographs of his own four daughters line the bookshelf behind where I sit. He points to them proudly. Despite all of the distance that looms between children and their parents in any profession, and despite all the time he spent at the office, one of Dr. Goldsmith’s daughters has decided to become a pediatrician. He’s inspired. I’m grateful. Clearly the message came through: the work doctors do is unparalleled. And despite the incredible challenges—sometimes because of them—so are the rewards.