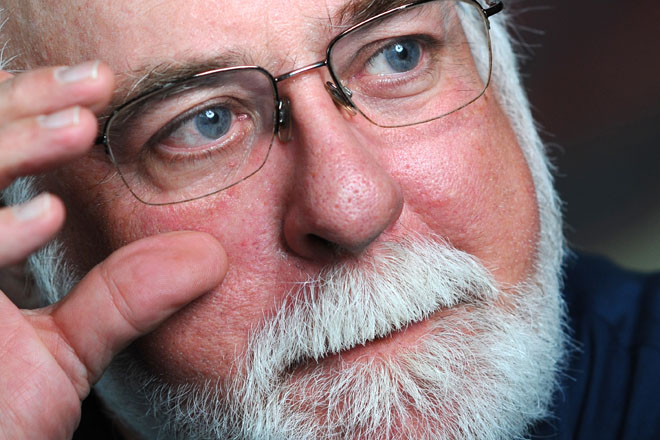

"Altitude Lou" McNally

Maine's best-known weatherman's meteoric rise

Maine’s best-known weatherman’s meteoric rise.

I vividly remember my first encounter with “Altitude Lou” McNally in May 1979 on Hurricane Island; he was leading a discussion on weather for a group of hardened Outward Bound sailors.

McNally described the meteorology behind nautical folk wisdom like “red sky in morning, sailors take warning,” and alerted us about what a sun dog, or a ring around the sun, foretold. McNally not only explained how the giant weather system works, but helped us understand that we all can learn some basic forecasting skills by watching the sky. McNally is an unforgettable personality, and those who have followed him on radio and television can attest to his endlessly amusing and colorful turns of phrase.

McNally’s experience with weather forecasting began as a young man when he was running a land surveying crew on Cape Cod. “I was crew chief and I’m the one that has to make the decision about whether to go out in the field or stay in the office. I was getting my forecasts from Don Kent at WBZ radio and his forecast would be something like, ‘variable cloudiness with a 50-percent chance of rain,’ and I’d be left wondering, do we go out or not? Because if I am out in the field with a $15,000 theodolite and the sky opens up, the theodolite gets the poncho.”

However, when “one of those myriad little recessions hit Cape Cod,” to use McNally’s phrase, he was laid off. He reasoned that he could become a better surveyor by learning how to forecast the weather. So he enrolled in a program at Belknap College in Center Harbor, New Hampshire, which he says was a school that “actually taught you how to forecast as opposed to learning differential equations.” He finished up his meteorology degree at Lyndon State College in Vermont.

While at Lyndon State, McNally started a five-minute forecast segment on the college television station. One month before his graduation, he heard about an opening for a weatherman at WCSH in Portland and he drove to Maine for an audition, one of two finalists for the position. After the audition, the news director offered him the job and told him to report to work the following Monday. When McNally arrived at the station’s human resources department, he remembers, “They looked at me and said, ‘who are you?’” McNally proudly told them he was the new weatherman who had just been hired. Oh, he was told, the previous news director was fired over the weekend and the new director had hired the other candidate. “Great start to my career,” McNally thought.

A few months later, McNally packed his belongings and headed to Freeport, Maine, where a good friend told him it was easy to find work. McNally got a job assembling lobster traps at the Marcraft Company while the crew listened to the WBLM morning radio show. “The morning guys just massacred the weather—it was a comedy act. So I wrote a letter to J.J. Jeffrey, the owner of the WBLM station, to say these guys doing the weather are terrible and I could do it better. About a week later, I got a call saying I could start Monday, but I had to come up with a name”—a radio handle.

“That weekend, I happened to be helping friends paint the bottom of a boat in South Freeport. We had a tent over the boat and there were lots of fumes and maybe a few beverages. We came up with all kinds of radio names, but the choices came down to the Cloud Prince or Altitude Lou. The Cloud Prince sounded a little arrogant, so I went with Altitude Lou. I started in March 1976,” Altitude Lou recalls, “and I have been on a Portland radio station ever since, for 39 years.” So has his signature sign-off, “And that’s the way it looks from here.”

Altitude Lou fit right in with the zany culture and irreverent banter at WBLM. The call letters (BLM) stood for the station’s hometown—Beautiful Lewiston Maine—and were featured in many of their jests. One of WBLM’s other radio personalities was Darrell Martinie, who dispensed astrological forecasts in a weatherman’s style and called himself the Cosmic Muffin, but whom Altitude Lou referred to as “the Cosmic Crouton—rest his soul.”

A few years into his radio career, McNally got a call from WGAN Channel 13 in Portland, which wanted to start a weekend newscast out of their studio in the Portland Press Herald building. He got the job, and in 1977 began another career as a TV weatherman. The WGAN job lasted a couple of years until he received a phone call from a headhunter. “They said, ‘we would like you to go to Des Moines, Iowa.’ And I thought I had been found by the industry!” says McNally chuckling.

McNally packed up his young family—a wife and two children at that point—and “dragged them” to the Midwest. “I was the chief meteorologist for WOI with an appointment at the University of Iowa. I had a staff of 12, all kinds of equipment, and I had minions running around in awe of my forecasting ability. It was the best job I ever had, but when you walked out the door, it was still Iowa—corn growing to 16 feet high in the summer, but so flat that you can see a train in the next county in the winter.” They decided to head back East and McNally found new jobs, first as a TV weatherman in Buffalo and then as one in Boston.

Back in Boston, McNally says, “I really started building up the radio business,” and he signed up more stations to air his signature forecasts. But McNally and his wife missed Maine and wanted to find a place where their children would receive a good education. They decided they would move back to Portland in 1986 to raise their children.

All the while more and more stations signed up for Altitude Lou’s witty weather banter. He had already signed up stations in Boston, Cape Cod, the Northeast, and beyond, and eventually added stations in Pittsburgh and even Mobile, Alabama. “We used to have a pretty big outfit, five or six people with teletypes and facsimile machines spitting out weather maps,” he recalls. McNally ended up with 66 radio clients and a consulting business on the side for airports and road crews, for which he forecasted such things as the proportions of salt needed in the sand mix.

He and his team also provided information on weather-related insurance claims and prepared expert testimony for an occasional murder case. They even started selling weather instruments out of the front door of their South Portland office.

That phase of McNally’s weather profession lasted about a decade until the media business was deregulated during the Reagan Administration in 1986. Prior to deregulation, media companies were not permitted to own more than six AM radio stations and six FM radio stations. But after deregulation, new rules eliminated the limits on the number of stations companies could own, and a few companies began buying up all the radio stations in local markets. Today “just four companies control 85 percent of the market,” McNally says. “They really cleaned up.” But the consolidation hurt independent weathermen like McNally.

Then in 1988, producers from Maine Public Broadcasting Network approached McNally, who had volunteered during the station’s annual TV fundraising auctions, and asked if he would be interested in hosting a new show, Made in Maine. The show “was an experiment,” recalls McNally. “The idea was to interview people who carved duck decoys or made toothpicks or Bean boots. But then what?” McNally wondered. “Made in Maine took off like a rocket and soon we had a pile two feet high of businesses that wanted to be covered.” McNally recalls fondly some of the Maine family businesses they profiled, like Raye’s Mustard in Eastport, with their “stone-ground mustard mill, where they sprinkle the mustard seeds on to huge stones, grind, and the mustard oozes out the side. It showed that with old technology and decent marketing, you could make a successful company.”

Some of the shows covered the state’s major employers, like Bath Iron Works, where McNally got to “smack the shims from under the Winston S. Churchill with a sledgehammer at 5 a.m.” to send the destroyer down the ways. Other shows profiled startups, including the show on which McNally interviewed “the nicest couple you would ever want to meet—Jim Stott and Jonathan King, who were in their second or third year of their Stonewall Kitchen business, having started selling jams off a red-checked tablecloth at a farmers’ market.” Their biggest product at the time was roasted garlic jam, “and I thought, ‘are you crazy?’” says McNally. Made in Maine ran for nineteen and a half years and produced 197 shows. McNally tells me almost nostalgically, “I can’t think of a road in Maine I haven’t been on.”

In the late 1980s, McNally says, “I started getting a lot of questions about climate I could not answer and I wanted to go back to get a master’s degree. So I drove up to Orono trying to figure out whether I could make this work. Hal Borns was running the Institute for Quaternary Studies at the time (the predecessor to the university’s present-day Climate Change Institute), and he was very encouraging of nontraditional students. I was doing a lot of radio at the time, but I was done by 7 a.m. So on Tuesdays and Thursdays, I would drive to Orono for classes and then stop in Auburn on the way back to do the 6 p.m. and 11 p.m. weather reports.”

McNally became interested in reconstructing weather of the past from diaries and news reports. “Diarists always mention the weather. No one had ever seen anything like that before,” he says. McNally looked at wheat prices in Delhi and the time of the cherry blossom bloom in Japan. He took a paleoclimatology course at University of Massachusetts at Amherst. It took him two hours and seven minutes to drive from Cape Elizabeth to Orono and two hours and fourteen minutes to drive to Amherst. “At a certain point, I had taken enough courses for a PhD and I decided to go on for the terminal degree—you know, ‘piled higher and deeper.’” In 2004, McNally was awarded his doctorate in interdisciplinary studies from the University of Maine—only the second student at the university to earn such a degree at the time.

In recent years, McNally has started a new career, teaching on the faculty at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Florida, and at the summer program at College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor. Hundreds of students at Embry-Riddle, who are studying for jobs such as airline pilots, air traffic controllers, or drone operators, not to mention weathermen and women for radio and television stations, must all take rigorous meteorology courses—many of them from McNally.

McNally receives high marks on the Rate My Professors website, with such accolades as “informative and funny; best of the best; absolutely hilarious; loves what he teaches.” Even though forecasting for television is one of the courses he teaches, McNally is circumspect about the profession. He quotes Hunter S. Thompson, perhaps apocryphally to his students: “The TV business is a cruel and shallow money trench…where thieves and pimps run free and good men die like dogs—and there’s also a negative side.’”

McNally’s career has taken him far and wide, but his roots in and attachment to Maine run deep. It is the place he always returns, not only because his four children and four grandchildren are in Maine, but also because “you have to dig a little deeper here. It’s hardscrabble for most people. Less is taken for granted. There’s this spirit that no matter what happens, I am going to make it work—it is only a question of how long it’s going to take. There’s a lot of creativity in this state, even if people have to leave every once in a while.”

At this stage of his life, McNally does not see his golden years beckoning. Instead, he has a current invitation to help start up the new master’s program at Unity College while also teaching online at the University of Maine, Machias, and holding down an appointment as research assistant professor at the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine, Orono. “I am not done yet,” says McNally, “there’s more left for me to do.” And— as McNally would say—that’s the way it looks from here.