Beauty and the Brain

When I was in junior high school, my friend Beth gave a presentation about artist Andrew Wyeth and his connection to Maine. As a twelve-year-old, I was painfully inept at drawing and painting and was somewhat skeptical about the relevance of art to my young life. Then Beth showed us Christina’s World. I was unexpectedly moved by Wyeth’s depiction of his Cushing neighbor, Christina Olson. Clad in a pale pink dress, she sprawled awkwardly on her side at the edge of a vast brown field. I sensed her isolation, as she looked toward her family’s rough-hewn farm in the distance. I felt the dry grass that scratched her palms and the hard- packed soil pressed against her hips.

How did Wyeth so effectively communicate with an untrained adolescent through his painting of Olson? According to Bates College professor William Seeley, humans are primed to respond to art. Seeley’s educational focus is cognitive science and the philosophy of art and the mind, and he is particularly interested in the neuroscience of art—how our brains engage with what we see. “Artworks are attentional engines,” says Seeley. “Artists provide us with abstract elements that naturally capture the attention of viewers.” Elements such as light, color, and landscape trigger the brain—and possibly nerve pathways throughout the body—to respond in unique ways depending on our previous experiences and what we bring from our own life to a piece of art. “What we know always influences how we perceive the world,” says Seeley. “It is an active process.” As a twelve-year-old, I may not have been familiar with Wyeth, but I understood the transitional nature of the body and the feeling of soil against my skin. This enabled me to connect with the painting of Christina Olson.

From a young age, most of us also have a sense of what is considered beautiful. When it comes to people, we have a predilection for those who have symmetrical faces. This is likely due to the biological advantage associated with symmetry. “This preference has value for us,” says Seeley. “A symmetrical face is a marker of a good immune system. It has value at an evolutionary level.” On a larger scale, we are attracted to places of beauty, in part because they offer benefits associated with a more amenable living situation. Water is one important element. Not only do we need water to drink, but we also need it for farming, fishing, and feeding our livestock. Maine, adjacent to the ocean, and home to lakes, rivers, and streams, has always offered a competitive advantage over other more arid locations. We have an affinity for that which sustains us: multiple studies, including one done in 2010 by the European Centre for Environment and Human Health, show that we actually prefer photographs that involve a water component over those that do not.

“For neuroscientists working on how we engage with art, the concept of beauty is important,” says Seeley. “It gives us an aesthetic experience that is pleasing and rewarding.” This aesthetic experience causes the brain to react, which can be verified using techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Engaging with things that we find pleasing causes the brain to “light up” on fMRI. This emerging field is known as “neuroaesthetics.” In addition to stimulating the parts of the brain related to vision, hearing, and other senses—and the parts of the brain that help us understand what we are seeing (also called cognition)—it should come as no surprise that pleasurable images, such as symmetrical faces, activate the emotional center of the brain, called the limbic system. This will provide interesting insights into what motivates us as humans, and why.

“We are drawn to various things because of the way they make us feel,” says Jane Bianco, associate curator at the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland. In 2014, Bianco created a show entitled Coloring Vision: From Impressionism to Modernism. The goal was to bypass people’s more intellectual way of responding to art, and instead appeal to their emotional response, by focusing on colors rather than a specific subject matter. “It was an invitation for people to find something they liked,” says Bianco. “To allow themselves to be attracted to something first, without being overwhelmed with information.”

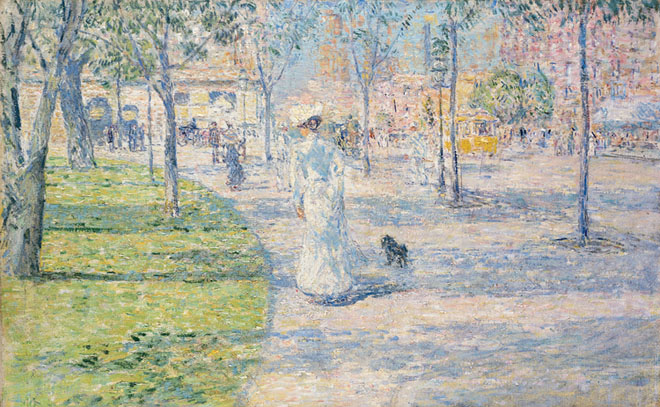

Coloring Vision featured artworks from painters as diverse as Childe Hassam, Rockwell Kent, Marsden Hartley, and Will Barnet. Bianco chose the works to represent a broad variety of color effects, light, and composition. The first pieces in the show were done by Impressionist painters, as this group had taken the study of color and light to a new level during the early nineteenth century. The shift in style was due to a new technology at the time—tubes of paint—which allowed artists to leave the studio and work en plein air. They were able to capture shifting light and the colors of nature while working outside.

Bianco describes Union Square in Spring, a piece by painter Childe Hassam, as one example of this type of work. Hassam had a studio in New York, close to Union Square. Like the popular park scenes created by French Impressionist Claude Monet, Hassam’s Union Square setting represented the changeable nature of this location during different seasons of the year. The painting features a woman walking her dog near a park. The individual brushstrokes of the painting evoke the bright, diffuse sunlight of spring. “Looking at the pastel pinks and baby blues, we begin to see this scene on the painter’s terms,” says Bianco. “The painting causes us to adjust our vision to its high-keyed color to read as brilliant light that unifies the figures and their setting.”

Artist George Bellows’s Sea in Fog was painted on Monhegan Island in 1913. According to Bianco, the deep teal greens and grays show his understanding of the energetic nature of water as the surf crashes against rocks on the shore. “It pulses with ever-changing color and suggests sensations that continue to echo in the mind: sounds of deep, cold water pounding against slippery hard rock—and the damp feel of heavy fog descending upon the surf.”

It is not simply that we feel ourselves emotionally connected to the surfside paintings of George Bellows or the New York City vistas of Childe Hassam—we may also experience an interesting after- effect. Bianco calls it “postcard vision,” which is the ability to see a real-life scene as it might have been interpreted by an artist or a photographer. Thus, artists have the ability to influence how we experience the world long after we have ceased to view their works.

Not only are artists, and art, coloring our vision, they are also potentially influencing our every sensation, thought, and memory— across disciplines. Neuroscientists are currently investigating how the brain engages with dance, music, film, and other modalities. “Why, as researchers, should we only learn one methodology and limit ourselves?” asks Seeley. “Cognitive science is born of the idea that you invite a bunch of people to the table and ask them to share their solutions.”

Bianco, herself an artist, reminds us that we need not be painters, filmmakers, or musicians to find creative stimulation. “Art can be all kinds of creative tasks,” says Bianco. “It can be cooking, gardening, or arranging things around us. It is not relegated to the museum.”

I cannot help but agree with Bianco. Although my painting and drawing skills have shown little improvement, I have found great joy in creatively doctoring, parenting, and occasionally picking up a singing gig at a local cafe. I’ve also come to appreciate those who create in ways that I cannot. Decades after Beth’s presentation, I saw Christina’s World in person at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. I imagined myself back in the school library, hearing about Wyeth for the first time, and once again felt the hard soil of Cushing under Christina’s body. I became the unexpectedly inspired twelve- year-old that I once was, and will always be.