The Wild Blueberry Yonder

How the wild Maine blueberry became and international health icon.

In the summer of 1974 I was living in a small cabin in Township 7, the southernmost unnamed township in Maine, between Steuben on the coast and Cherryfield on the Narraguagus River in Washington County. It was blueberry season and everyone on the Number Seven Road, where my cabin was located, was talking blueberries.

My neighbor, Old Ralph, was pushing 75 and his son, Ralph Jr., at some indeterminate age north of 50, owned a modest amount of family blueberry land. They had just finished harvesting their own land and were assembling a crew to rake on the barrens at Deblois, where Ralph Jr. had a contract with Jasper Wyman and Son, Maine’s largest blueberry company at the time. Was I interested? You bet.

The wild blueberry harvest in Washington County was the one time of year when almost anyone between six and 60 could earn a small pile of cash to spend like a grasshopper or save for the coming winter. I had not laid eyes on the barrens, but the description of an ocean of nearly flat sandy land covered in shades of pastel blue and the potential of collecting a winter’s earnings in a month’s time were instantly appealing.

One week later I was in the back of Ralph Jr.’s two-ton, stake-body truck with a motley crew of neighbors, lurching off Highway 193 onto dirt roads that curved around endless vistas of blueberry fields on the barrens. When we stopped, Ralph handed me a bucket and a blueberry rake. He explained that when I had filled my bucket, I was to bring it over to a hand-cranked winnowing machine to separate the leaves and stems from the berries and then pour the berries carefully into wooden boxes. For this, I would make $2.50 a box. Seemed simple enough.

Four decades later, recalling that grueling, backbreaking month I spent on the barrens, I wondered what had changed in Maine’s wild blueberry industry. It turns out, almost everything.

To begin my re-education, I returned to the Deblois barrens to meet with Darin Hammond, senior farm operations manager for Jasper Wyman and Son. Wyman’s, the oldest wild blueberry business in Maine, is still a family-owned company and the second-largest wild blueberry grower in the nation with thousands of acres in production, two processing plants, and employing hundreds of workers in seasonal and year-round jobs in Maine.

The barrens, Hammond explains, got their name because the nutrient-impoverished sandy soils left by the receding glacier would grow “nothing other than blueberries, sweet fern, scrub birch, and willows.” Wyman’s, like other growers, devised various means of dispensing with competing ferns, birch, and other weedy vegetation that can tolerate the scarce nutrients and limited moisture. Back in the 1970s growers on Maine’s 60,000 acres of blueberry land used to burn their fields every other year in order to stimulate the growth of more flowers and fruit per stem and get rid of competing vegetation. I can still picture little tongues of fire burning into the early evening on the hillsides as the smells wafted up through the yellow pall of smoke. But Hammond explains that by the late 1970s burning had become expensive and labor-intensive, and growers began searching for alternatives.

Blueberry growers turned to the University of Maine at Orono for help—and for a good reason. Ever since 1945 when members of the industry went to the Maine legislature and got a law passed that taxed blueberries and eventually established the Maine Wild Blueberry Commission, the organization has brought members of the blueberry industry together with researchers at the University of Maine “to promote the prosperity of the crop.” The result of the appeal has been a stunning success.

Compared to the summer I spent raking, the state’s blueberry harvest has more than quadrupled. Coming in at over 100 million pounds, 2014 was the second largest wild blueberry harvest in Maine’s history.

To get a deeper understanding of how the industry had thrived without me, I went to Orono to meet with Maine’s two most prominent blueberry experts, David Yarborough and Frank Drummond. Yarborough is a wild blueberry specialist and professor of horticulture, but more importantly is an expert in weed ecology. Drummond is a professor of insect ecology, and more specifically a bee expert.

Careful research the university conducted prior to the 1970s, says Yarborough, revealed that when growers were burning blueberry fields, “they were literally incinerating the roots, so we started researching whether growers could use mowers instead to prune the wild blueberry plants.” Slowly experiments with mechanical harvesters and years of “de-rocking” fields enabled growers to use equipment that increased the wild blueberry harvest, beginning in the 1980s. In addition, processors like Wyman’s were investing in new freezing techniques where each blueberry could be frozen individually rather than in a solid block—a process called individual frozen quantity (IFQ). IFQs, according to Wyman’s Hammond, “opened the door to increased sales.”

Nancy McBrady, who is currently the executive director of the Maine Wild Blueberry Commission, says of Maine’s wild blueberry industry, “it’s almost like it is Maine’s best kept secret. We grow a very special product, but a lot of people don’t know the difference between a wild blueberry and a cultivated one.” (Hint: the fat watery ones with less flavor are the cultivated ones.) In her position McBrady acts as a voice for the industry and points out that, “When we started growing more berries, we had to sell more berries.” So Maine’s Wild Blueberry Commission began searching for more effective marketing strategies. Added to this challenge was the fact that cultivated blueberries from other states are grown in large numbers and dwarf the production of wild blueberries.

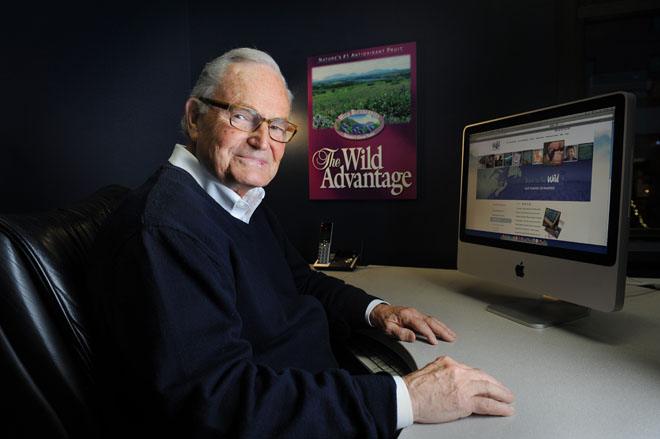

In 1992, members of Maine’s Wild Blueberry Commission listened to a presentation from a marketing strategist, John Sauvé, who suggested the industry needed to position itself somewhere in the intermediate ground between its traditional image as a commodity—tens of millions of pounds of undifferentiated product—and a single unified brand, which competing processors were hardly in a position to consider. So Sauvé proposed that the industry “think in terms of a strategy to focus on taste as the differentiator.” After all, wild blueberries have always won every taste test against their cultivated cousins. The commission was impressed and hired Sauvé as its executive director in 1993 to begin implementing a new branding strategy.

A few years later a funny thing happened. David Yarborough faxed Sauvé an article from an obscure agricultural research magazine. The article, titled “Plant Pigments Paint a Rainbow of Antioxidants,” showed that blueberries had the highest amount of antioxidants tested among 20 different fruits and vegetables. Another study demonstrated that old rats could solve cognitive puzzles as well as younger rats after being fed high volumes of blueberry phytochemicals. Sauvé thought, “Oh my, we have a story.”

Next Sauvé went to Japan, one of the most health-conscious food markets in the world, to a trade show where he extolled the health virtues of Maine’s wild blueberries. That is when “everything went crazy,” says Sauvé. When he returned, he told the commission he thought Japan could be a 20-million- pound market. But he was wrong. Maine had been exporting three million pounds

of blueberries to Japan, but two years later that figure had grown to 30 million. “I am a believer that when opportunity knocks, you open the door,” says Sauvé. “But they threw something through the door, and we just picked it up.”

“The cultivated blueberry industry didn’t invest in the antioxidant strategy,” says Sauvé. “But we did. In 1997, 1998, 1999, and 2000, half of our resources went into repositioning the industry—not just business to business, but building value- added products to market to consumers. In those years, we went from ‘something in a muffin’ to a health icon.”

Since then, the industry has doubled down on health and taste as the key marketing advantages of Maine’s wild blueberries, according to Mike Collins of Ethos Marketing and Design, the industry’s current branding, marketing, and advertising agency. Collins emphasizes that not all blueberries are created equal. Maine’s blueberries were not planted, but “grow wild where Mother Nature put them over 10,000 years ago.” With thousands of different varieties, they present a “bouquet of flavors” (almost like Bordeaux wines) that cultivated blueberries simply cannot match, regardless of whether you have heard of natural phytochemicals or antioxidants.

The current challenge Maine’s wild blueberry industry faces came from the hardest workers in the blueberry fields: the honeybees that pollinate the flowers that become fruit. When I drove through the barrens in early June, shortly after peak bloom, most bees had recently departed from Maine in “trains of 18-wheelers,” according to Hammond. An estimated 4.2 billion bees in 84,000 hives were required to pollinate Maine’s wild blueberry crop in 2014. Most of the bees that pollinate Maine’s wild blueberries travel all over the country from crop to crop. Many of the hives trucked into Maine had arrived from places like the California almond groves or Southern fruit groves before heading off to apple orchards or cranberry bogs after Maine blueberries in June.

According to Frank Drummond, Maine’s wild blueberries “are 100-percent reliant on bee pollination,” which is of deep concern to growers because “honeybees are in crisis.” Honeybee populations are plummeting all over the country due to a mysterious condition once called colony collapse and now referred to as colony loss, where entire colonies suddenly get sick and die. This phenomenon is now known to be due to multiple stressors, including disease-causing agents, parasites, low genetic diversity in honeybee stocks, heat stress, intercontinental trucking stress, and supplemental feeding with nutrient- poor foods such as corn syrup. In 2014, Drummond says, average losses among beekeepers went up 40 percent nationwide.

Much of the news coverage of colony loss points the finger at intensive agricultural use of pesticides, especially a new class of pesticides called neonicotinoids. Drummond believes the reasons are more complex, including the effects of an introduced parasitic mite that compromises the bees’ immune systems. “It’s like they have AIDS,” he explains, which makes them susceptible to a host of other diseases. Then pesticides, including the neonicotinoid insecticides, are taken into the nectar and pollen where bees with compromised immune systems are feeding, and the interaction of all these effects can precipitate a colony collapse over time, making a specific diagnosis of the cause extremely difficult.

The confluence of the Maine wild blueberry’s health food story and the colony loss disasters affecting honeybees has led some growers and one processor to start hedging their bets by investing in organic wild blueberry production. Todd Merrill, who left a software development job in southern Maine to return to his roots, is the president of another family-owned Maine blueberry business, and a member of the fifth generation to run Merrill Blueberry Farms in Ellsworth.

I meet Merrill at the company’s processing plant just before the harvest begins to shift into high gear. Merrill tells me that five years earlier a grower from Columbia Falls with 30 to 40 acres of wild blueberry fields had asked him if he had a market to sell wild organic blueberries. His berries came from fields that had not been sprayed for three years and had been certified by Maine Organic Farmers and Growers Association (MOFGA). At the time, Merrill says, “a few others had been doing well selling fresh pints of organic berries, but it was not a primary source of income for anyone.” Merrill tells me he was willing to become the first company in the country to process organic wild blueberries for the frozen market, partly because it was 2009. “The economy was horrible, so I beat the streets and turned over rocks looking for markets.”

The second year he added a few more organic wild blueberry growers—mostly smaller ones with five to ten acres. Merrill’s first customers were bakeries and restaurants, and he sold frozen organic wild blueberries box by box, then pallet by pallet, and finally, after 2012, he could sell a full trailer load. Last year organic wild blueberries were a 300,000-pound crop, which, he points out “is only three to five percent of my total annual crop.” But he adds, “I sold out of organic berries a lot sooner.” Merrill’s also allows organic growers to “buy back” their own berries so they can sell them to their own customers. This helps growers maintain their local markets for organic wild blueberries, and allows Merrill to concentrate on higher- volume sales. “I am doing everything I can to help,” says Merrill.

A recent study of the wild blueberry’s economic impact in Maine showed that the industry has grown to over $250 million, including $173 million of direct sales, and employing over 2,500 in seasonal and year-round jobs. Although the industry is now international in scope, there are plenty of wild blueberry products available throughout Maine, including blueberry wine, smoothies, buckle, and yogurt. But my favorite way to enjoy them is to stop by Helen’s Restaurant in Machias (newly reopened), tuck into one of Helen’s famous homemade blueberry pies, and be thankful I did not have to rake them.