A Walk with the Woods

A Walk with the Woods

We join veteran guide Raymond Reitze on ponds and bog trails in western Maine and at his farm in Canaan, hoping to glean bits of this gentle man’s wisdom from his lifetime of living simply with nature.

by Sandy Lang

Photography by Peter Frank Edwards

Issue: December 2020

He doesn’t dream of distant travel. “Eden is right here. Everything you need is outside,” says Raymond Reitze as he stands in a forest of birch and ash. Sometimes he leans against a tree or slides down to sit at its base, to watch and listen awhile. He can spend hours, days this way; he recounts how he once spent 33 days alone, simply walking the woods of Maine.

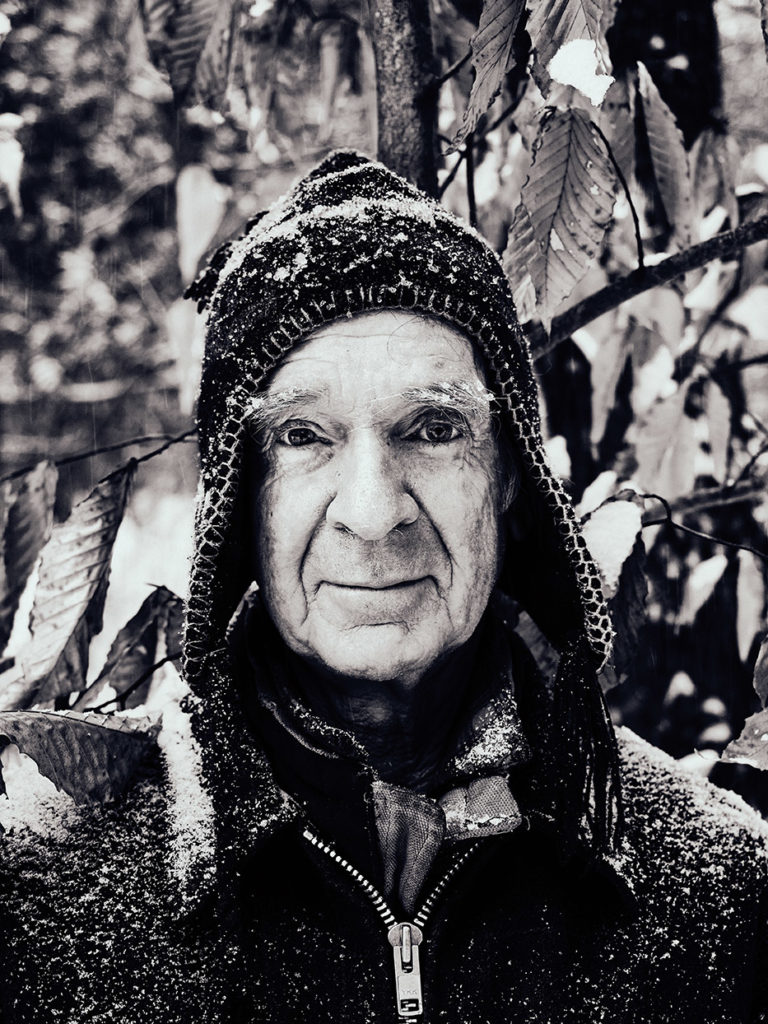

At 74, Reitze’s stay-close-to-home philosophy sounds on-trend for our times in 2020. But this Master Maine Guide is anything but trendy. He has been observing, learning, and forming his nature-centric lifeways since his Maine boyhood.

A guide, teacher, philosopher, and writer, Reitze espouses a simple, nature-based way of living, and he speaks with a clear-eyed gentleness that makes you want to listen. “Often I run into wealthy people who are stressed out—people who act as if the purpose of life is to pile up mountains of money,” he says. He sees things differently: “Life is a gift, and happiness is something you can’t buy.”

Photographer Peter Frank Edwards and I first meet Reitze on a bright fall morning after driving to his farm in Canaan, following directions he gave us that include looking for signs to a U-pick blueberry patch and going slowly along a rutted dirt road across a small wooden bridge.

Reitze built that bridge. In prior decades he and his wife, Nancy, raised cows on these 180 acres of woodlands and pasture. Then he shifted to guiding canoe trips and camping excursions—including some 150 trips on the Allagash River. These days, Reitze’s focus is on sharing and teaching. Younger guides and people who want to learn more about living on and with the land seek him out. They often call him “Grandfather Ray” or “Old Turtle” out of respect for his wisdom and his knowledge of primitive skills and crafts. He’s humbled by the attention. “I’m more comfortable sitting among the trees talking to the birds and bees,” he says, “but people keep coming by.”

On this day, Becca Houghton and Dave Boynton will be visiting from New Hampshire, and they arrive just after we park. Both have been studying to become Registered Maine Guides, and they met Reitze at last year’s Common Ground Country Fair. “We want to learn more from him about wilderness living skills,” says Boynton.

Reitze himself soon appears, driving up in an over-sized farm truck with a rumbling diesel engine and a dump truck bed. He hops down from the big truck’s cab—all five feet eight inches and 140 pounds of him— and he’s smiling from beneath a wide-brimmed hat that’s a bit rumpled. He’s wearing canvas work pants, a flannel shirt, and L.L.Bean boots. With a natural ease and slow pace, he sets an unhurried tone to the outing right away. “When someone is ‘late,’ they worry,” he says. “But we’ll get going on time—whatever time that is.” Reitze moves deliberately from task to task, and notes that he always leaves space for weather delays or a break for tea or “to sit with a friend, even if we don’t talk.”

Today’s plan is to spend some time canoe poling and exploring a bog that’s north of Stratton, almost to the Quebec border. It will be a nearly three-hour drive each way, but it’s a blue-sky October day, and all of us are game.

As we ramble northwest, farther into western Maine, whole ridges appear backlit in electric shades of orange, red, and yellow. Fall color is at its peak as we drive through Kingfield and along the Carrabassett River, which Reitze sometimes canoes in the spring.

“Look,” he says, pointing to line of trees. “That color will be gone in a week. People say, ‘I’ll catch it next year.’ But what if you’re not here next year?”

Reitze stopping for a lunch break after a morning of canoeing on the Chain of Ponds in Franklin County.

“It’s like I’m standing on a great big fish,” Reitze says, standing astride the gunwales of his canoe. He built the canoe and carved the spruce wood pole.

Poling the Ponds

Our destination is the Chain of Ponds Public Reserved Land, which includes Natanis, Long, Bag, and Lower Ponds, all joined by narrow thoroughfares. Off scenic Route 27 in northern Franklin County, the ponds are less than an hour’s drive from Sugarloaf Resort, past Stratton and Eustis heading north.

This is familiar territory for Reitze. The eldest of six children, he grew up in rural Buxton in the 1950s and ’60s, and in summertime his family would go to the Chain of Ponds, which he’d explore by canoe. He learned wilderness skills and how to live off the land from a Mi’kmaq elder in the farm community of his boyhood. And Reitze has built upon those skills throughout his life, making his own canoes and carving the paddles and poles. He built the canoe he’s paddling now, based on an early-1900s birch-bark design.

For the canoe poles, Reitze explains, he uses spruce wood for its flexibility, and he makes them thicker and weighted on one end—as opposed to the New Brunswick style, which he describes as heaviest in the middle and tapered on the ends. Canoe poling requires standing up in the canoe, holding the pole vertically above the waterline on one side of the canoe, and pushing it into the river or pond’s floor to set it. Reitze demonstrates, drawing the pole back upward in his hands smoothly as the boat moves forward then dropping the pole again. He moves to stand atop the gunwales as he poles along, saying, “It’s like I’m standing on a great big fish.”

The shallow pond’s bottom is sandy, and the water is clear and calm. Reitze says the Chain of Ponds is a good place to bring beginners. We each take a turn in the canoe—but standing on the bottom, not the gunwales. When it’s my turn, the initial standing and balancing feels akin to standing on a paddleboard. I feel the difference in creating motion from the energy of pushing off of the pond’s bottom rather than paddling, and I like the vantage point of standing, looking across the water toward the autumn color show on mountainsides and along the far shore.

The day’s lessons aren’t just in canoeing. When we pull our boats onto a beach, Reitze notices animal trails in the tall grass behind us that he says looks like beaver activity, and he follows the trail a few yards to investigate. Later, when we’re all back out on the water paddling canoes, he points to dark, dirt-like clumps growing on the trunks of birch trees just up the bank and asks, “Do you know about chaga?” I don’t, and he explains how pieces of the mushroom-like chaga can be used as tinder, and then embers can be carried on a hike or canoe trip inside a shell and used to start another campfire later. “Just blow on it for a flame,” he says, “and what’s left you can use for tea.”

Stepping carefully through the green, layered floor of a bog north of Eustis, Reitze identifies plants like this bog Labrador tea.

Joining him are Becca Houghton and Dave Boynton, both studying to be Maine Guides.

Reitze uses sight, smell, touch, and taste to identify plants.

Goldthread and Bog Berries

Creeping snowberry tastes like wintergreen. I am learning this after we’ve put the canoes back in the truck and have gone to explore a nearby bog on foot. Reitze encourages us to pluck one of the small white berries growing close to the ground. One by one, we each pop the berries into our mouths to experience the minty-cool burst. “Doesn’t that knock your socks off?” he asks. Every step or two, Reitze finds more plant life of interest to show us. He points out a wild rhododendron known as bog Labrador tea (pahsipokehsok in Passamaquoddy) because traditionally the fragrant leaves have been used in tea by native peoples of the Northeast.

He shows us goldthread, a perennial herb with roots that do look like yellow-gold thread, said to have medicinal qualities. He points out sphagnum moss, which was historically used as an anti-septic, and a gray-green, airy lichen (kind of like frisée) that hangs, curtain-like, from branches and whose presence indicates “very clean air.” Step by step, we see the profusion of mosses, plants, herbs, and lichens around us through Reitze’s lens of wonder and understanding.

Among his fall chores back at the farm, he says, is gathering herbaceous plants to dry and chop for tinctures and put in jars for use during the year. Thistle, burdock, dandelion, yellow dock, knotweed, yarrow—all have traditional medicinal uses.

Winter Camp

The seesaw of sap season has already begun when we visit Reitze next. Just mid-February, nights of freezing temperatures have been followed lately by unseasonably early thawing. Usually at this time there are about four feet of snow in the woods of his Canaan farm, Reitze says, but there are only 16 to 18 inches out here now. It’s pretty, though, and he’s got a winter camp set up—a canvas shelter about a half-mile walk from the house.

Reitze grabs his snowshoes before we go. He made the pair, along with his own pack baskets and toboggan. He also built a hogan, a traditional Navajo-design log house, where he and Nancy lived for decades, and the newer home where they now live, a cabin outfitted with solar power and a woodstove for heat. No need for electric power service here.

We follow Reitze on a trek through the woods to the camp, which he and Nancy erected on a bed of fresh-cut balsam fir boughs. Temperatures are in the mid-20s, and it’s a relief to see the shelter and step inside just as snow starts falling. There’s a lightweight titanium woodstove in here, but it’s not lit just now. Instead, we’re just enjoying being out of the wind and snow. We each sit on the branches with our legs folded. I keep wiggling my toes to try to keep them warm, and the scent of balsam fills my head and lungs.

Another visitor, Ruth Ann Keister from Norridgewock, is joining us this time. Reitze begins talking about knots, and ties a couple with a rope around the center wooden pole of the tent: a half hitch and a trucker’s hitch. Earlier, he traced his foot onto a piece of scrap fabric to demonstrate how to make a pattern for “an easy moccasin” of leather or suede. Whenever he shares knowledge or teaches such off-the-grid skills, it’s part of passing on a legacy. That’s something he’s been thinking of recently, as he grows older.

Later, we are standing in the falling snow as Reitze cuts yellow birch twigs for tea he’ll steep on the woodstove. “To me, a legacy is leaving something precious for the world,” Reitze says. “Anybody can take any piece of it, and do with it what they like.”

The ground below the tent is carpeted with freshly cut balsam fir boughs. Reitze practices knot tying with visitor Ruth Ann Keister.

The tent has no floor, but it has a lightweight woodstove.

Many foraged and found botanicals fill shelves in the pantry.

Reitze always has a favorite antler-handled knife on hand to collect new cuttings.

Meet Grandfather Ray, Old Turtle

If you’d like to learn more about the philosophy and teachings of Master Maine Guide Raymond Reitze, check out:

And We Shall Cast Rainbows Upon the Land, a self-published 2004 book of stories, philosophy, and poetry.

Guided, an award-winning independent short film about Ray Reitze released in 2016 by Seedlight Pictures, available on Vimeo and at seedlightpictures.com.

Reitze’s series of monthly meditations, the “Heart Teachings,” are open to all, and he’s planning a series of guided trips for 2021. Visit @teachinglodge on Facebook or call 207.426.8138 for more information.

to sip. For real change, Reitze says, “Follow your heart, not your head. Forget national politics

and focus on what’s happening locally. Buy from local businesses. For food, get really local. Grow what you can. Make electricity in your own yard. That’s how we need to begin to think.”