The Beloved Community

FEATURE-November2013

By Jaed Coffin

Photographs by Fred Field

Tree Street Youth, The Maine Community Foundation, and the love of a single neighborhood

On a cloudy afternoon in mid-September, I drive into downtown Lewiston via Route 196, onto East Avenue, onto Bartlett Street, past an industrial neighborhood of auto repair shops, an Italian bakery, Mailhot’s sausage warehouse, the Lewiston public works facility, several vacant commercial properties, and a halal food store. At the top of the hill, where Bartlett meets Birch, is a gateway of sorts, to a neighborhood that few of us in Maine know much about. The buildings here—aging multiplexes four and five stories tall—were built during a period when some ten thousand Franco-American immigrants came to this city to work in the local textile mills. Now, the buildings are home to families of the roughly 5,000 Somali who, fleeing civil war, have resettled in this neighborhood, on these streets that are named after the trees of New England: Pine, Birch, Spruce, Maple, Walnut, Ash.

To the east, at the bottom of a hill on Birch Street, is Longley Elementary School, where the children of this tight-knit community—who often converse with their parents in mixtures of French, Somali, and Arabic—are enrolled in English language-learner programs. Across the street, on the corner of Birch and Howe, is a white and somewhat dilapidated one-story commercial building that was once a paint shop, and then a preschool. A small sign in the parking lot reveals the building’s current use: Tree Street Youth Community Center. Academics, Art, Athletics.

Julia Sleeper is the 27-year-old executive director of Tree Street, who founded the center back in 2009. From Brewer, of Lebanese heritage, a graduate of the John Bapst class of 2004, of the Bates College class of 2008, of the USM master’s in leadership class of 2011, Sleeper is a woman whom the children of this dynamic neighborhood refer to, simply, as “Julia.” When they talk about the center, they don’t usually call it Tree Street; instead, they tell their parents, “I’m going to Julia’s.”

At 3:30 p.m., not long after the last bell rings at Longley Elementary School, Sleeper crosses Birch Street, and guides the children into her domain. Now they are playing basketball, now they are chucking footballs, now they are playing tag and laughing and running in circles. Inside, they’re playing Ping-Pong, dancing the cha-cha slide in five lines of eight; they’re working on art projects and taking yoga classes from local volunteers; they’re getting help with their homework from local college students and Street Leaders—young people from this community who, often having come through Julia’s program themselves, are now charged with the responsibility of being mentors. The Tree Street center is a maze of rooms and hallways, decorated with donated couches and chairs, the walls adorned in colorfully painted words—HOPE, DREAM, LOVE, ASPIRE, JOY, PEACE. Julia’s favorite: WE BELIEVE IN TREE.

“Sometimes it’s like herding cats,” Sleeper says, as she moves through the hallways, directing children of younger ages to one room, older ones to another, keeping track of who’s coming and who’s going with an attendance app on her phone.

Sleeper sometimes describes the children who come to her center as “underprivileged” or “at risk” or “vulnerable” or by any of the terms of the social-service lexicon that never quite seem to fit. But it’s easier for Sleeper to speak about the Tree Street kids—as she does, over and over again—with this refrain: “they’ve got a lot goin’ on.”

By a lot going on, she means that many of them have come to Lewiston midway through their young lives, after having lived in several other resettlement cities as victims of circumstances that only decades from now will they be able to understand. But today, as they learn English, as they become more confusingly American with every breath of Lewiston air, they come to Julia’s to play, to create, to feel safe, to belong.

The origin story of Tree Street has the ring of a modern fairy tale: during her sophomore year at Bates, when Sleeper found herself “wandering” toward choosing a major, she took an education class. While putting in contact hours at the local public schools and other community organizations, Sleeper found herself drawn to the Somali community for reasons she hadn’t expected. Growing up in Brewer with deep Lebanese roots—“I got all the dark genes,” Sleeper says of herself—she saw in the struggles of her clients unarticulated shades of her own Maine experience. One afternoon, while passing an unoccupied building on Howe Street, Sleeper had a vision. She put the landlord’s number in her cell phone under the name: “WANT THIS.”

After graduating with degrees in education and psychology, Sleeper started a five-week summer camp at the vacant building, renting on a short-term lease. But at the end of the summer, she wasn’t satisfied, so she began the long journey of turning her camp into a year-long program.

“People in this town were ready for it,” Sleeper says. “The community was ready for it. People kept emerging.”

Lawyers who’d heard of Tree Street offered pro bono services to help her get registered as a nonprofit; grant writers volunteered their time, local businesses made donations. One of the most essential steps in making Tree Street a sustainable service was a grant that Sleeper received from the Maine Community Foundation, through the People of Color Fund. When Julia speaks about the effect that this grant had on her center, her tone shifts. “We couldn’t have started Tree Street without it,” she says. “If they hadn’t been willing to invest in us from that early point, we never would have taken off.”

Earlier that week, I met with the president of the Maine Community Foundation, Meredith Jones, at her home in Belfast. A small woman with a big smile and bright eyes, Jones had recently returned from a week-long hiking trip in the Grand Tetons. As we sat in her kitchen eating apples and peaches and drinking iced tea, Jones spoke energetically about the tripartite goals of MCF: to support the building of leadership, education, and community development. This year, Jones reported, MCF is stronger than ever. Currently, the foundation is supported by over $330 million in assets—a sum comprised mostly of funds set up by philanthropic families and individuals who wish to devote their wealth to the vitality of our state.

MCF’s purpose is to build the connections between these monies and the organizations that need them. “People want to give, and nonprofits want to do their work. Our job is to help them both,” Jones told me.

Since MCF opened its doors in 1983, they’ve awarded over $180 million in grants through 18 funding programs. Each year, MCF gives out 3,500 grants, some as small as $100, others as large as $7,500. When I asked Jones if there was a memorable application that captured the essence of what MCF does, she smiled.

“We once got a handwritten letter from a man asking for $650 so he could help local elementary school kids plant pumpkins.” That was a no-brainer, Jones recalls. “It just goes to show you the difference that a single individual can make when they have the confidence to take on important issues.”

In the case of the pumpkin farmer, he wanted to connect local kids to the land, to their agricultural heritage. In the case of MCF’s other grantees, who tackle everything from poverty to food stability to arts in schools, the goals are endless. When I asked Jones if she could think of an example right now that MCF was particularly proud of, she nodded, and said, “You know about Tree Street?”

I didn’t. Jones said that I needed to go see what was happening in Lewiston. Then she offered to make me a sandwich for the ride home, and hugged me goodbye.

In many ways, the movement of funding from a philanthropic individual’s donation into the life of a first-generation Somali child in Lewiston is a journey as labyrinthine as the halls of the Tree Street center.

The journey began with a $1 million donation made to MCF in 2007, on behalf of the Rock River Foundation—a pool of donors composed of philanthropists with a common goal of fostering racial equity. To manage that donation, MCF then created the People of Color Fund. Stefan Jackson, who has been involved in nonprofit management throughout the state, and who currently serves as executive director of Presumpscot Regional Land Trust, is one of the administrators of the People of Color Fund. Though Jackson isn’t able to offer names of individuals behind that initial donation to MCF, he assures me that if the names were made public “there wouldn’t be many surprises.”

In the last six years of the People of Color Fund, the Rock River donation has funded projects for Penobscot and Passamaquoddy tribal initiatives, Portland city schools language programs, the Centro Latino, the Museum of African Culture, and the Maine Migrant Health Program, which received funding to provide health services to migrant workers in rural counties.

What Jackson saw in Tree Street was a project that met all the criteria of the People of Color Fund. What drew him especially to Sleeper’s center were the “pedagogical values” and “pyramid model” of education, where a sense of leadership and responsibility was being passed down from one generation of learners to the next. The Street Leaders at Tree Street reminded Jackson of programs he’d worked with in outdoor education—the Nature Conservancy among them—where young people not only gathered essential experience, but also were trained on how to pass that experience down the line.

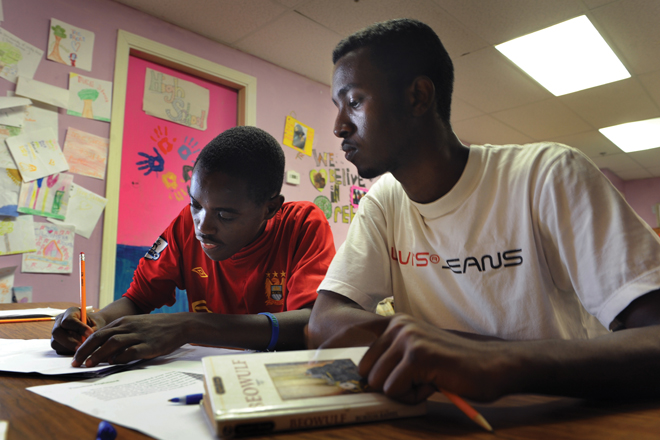

This afternoon, Mohamed, a senior at Lewiston High with a “90 GPA” who aspires to be the first person in his family to go to college, is helping Dalmar with his world history project—a timeline depicting the journey of his own life. On the line are marks for when Dalmar came to the United States, when he came to Lewiston, when he found his way to Tree Street this fall. Mohamed knows this project well: he excelled in the same class the year before, and now volunteers his time at Tree Street helping kids who, struggling with their English, are still trying to get their bearings. While Dalmar puts the finishing touches on his project, Mohamed reads through a copy of Beowulf, a story he describes as about a brave man who travels great distances to “prove himself in another country.”

By 5 p.m., a rainstorm sends all the kids inside. Mohamed and Dalmar are getting pegged with Ping-Pong balls, and Sleeper sighs. There’s so much more she wants to do here. She wants to own a building, to have designated areas for study and for play, to have more room, more money, to make Tree Street available for more kids. But for now, because of support from sources like the People of Color Fund, Sleeper says “we’re in progress.”

“I love them,” Sleeper tells me when I ask her why she does this. “This is what I was meant to do. To be that link, that push that gives these kids a voice.” She tells me that her first students are now seniors in college who come back to visit often, to apologize for the way they acted as children. But one of the central Tree Street policies is that there’s “endless love” and “100 percent acceptance, even in the rough times.”

Then a little girl runs up to her side and wraps her arms around Sleeper’s leg. Her name is Ubah but at Tree Street, she tells me, everyone knows her by her nickname: “Little Julia.” I ask her why she’s called that: “Because,” she says, “I’m a future leader.”