Art for an Anxious Time

At the Center for Maine Contemporary Art’s Biennial, themes of anxiety and survival run through the work of 34 artists.

(photo courtesy of artist)

The energy at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art (CMCA) Biennial is strong, bright, and discordant. A sense of restlessness permeates the collective narrative of the artwork, and a sense of anxiety and survival dominates. These have become the overriding feelings of a time of global pandemic, racial inequities, economic uncertainty, and political upheaval, and the CMCA Biennial illustrates how the resulting tensions can take form in artists’ work.

The group show of 34 of Maine’s most intriguing creative voices opens in the Rockland institution’s light-filled Marilyn Moss Rockefeller Lobby. A large, abstract wall painting by Jenny McGee Dougherty sets the tone, with tumbling forms that propel the viewer toward the galleries, not allowing a sense of balance to settle. Her painting—Municipal (2020)—features blocky, quasi-geometrical shapes that seem to hover against a flat, pale ground. In the Karen and Rob Brace Hall, Fanny Brodar’s ecstatic, cartoonish paintings present bright abstraction and also depict sympathetic faces, such as that of Sesame Street’s Grover. Brodar’s work unpacks the imagery of popular culture in a manner that recalls dumping out a heavy knapsack. Line, texture, color, and form reach a proximity to chaos that transforms the paintings’ carefree imagery into something nearing violence. At the other end of the corridor, Isabelle Maschal O’Donnell’s stitched fabric pieces, in the form of quilted mosaics of jewel-colored cloth, radiate a kind of optimistic dystopian Modernism.

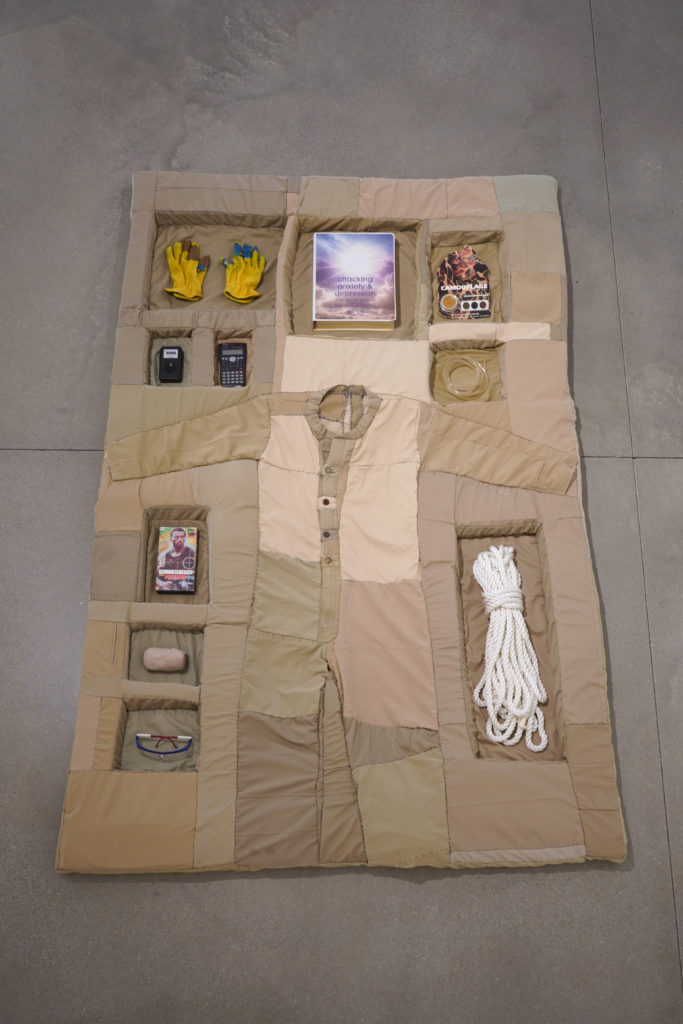

The atmosphere becomes more somber in the Guy D. Hughes Gallery. The paintings, photographs, and sculptures here act as a series of memento mori, standing guard over that which has been lost, or is in the process of being lost. Baxter Koziol’s work forms the narrative hinge in this sequence, allowing the viewer to imagine a world where anxiety and panic can be tamped down by constructing a proper garment or dwelling to contain these feelings. The Sequel Suit (2019), a wall-mounted sculpture, features a small sequence of brown suits sewed into and over one another to form a single composite garment, recalling the multiple copies of Joseph Beuys’s Felt Suit, which Beuys constructed in the 1970s for imaginary giant humans of the future. In the same spirit, Koziol’s work invites the viewer to envision the comfort his suits might bring to an unknown kind of wearer. Survival Blanket 1 (2020), the companion piece on the gallery floor, offers greater specificity. Within the niches in a large three-dimensional blanket, we find self-help books on tape to cure worry; a length of rope; VHS tapes; a camouflage face-paint kit; and other survival and escape aids. This is the key to the ideology of the 2020 Biennial: meeting anxiety head-on and surviving it with creativity. Koziol’s work simultaneously points to both the malady and a possible cure.

Baxter Koziol, Survival Blanket 1, 2020, used clothes, yarn, survival gear. (photo courtesy of CMCA)

Baxter Koziol, The Sequel Suit—The Sopranos (1999) Deep Blue Sea (1999) Adaptation (2002) Nightflyers (1987), 2019, used clothes, yarn. (photos courtesy of CMCA)

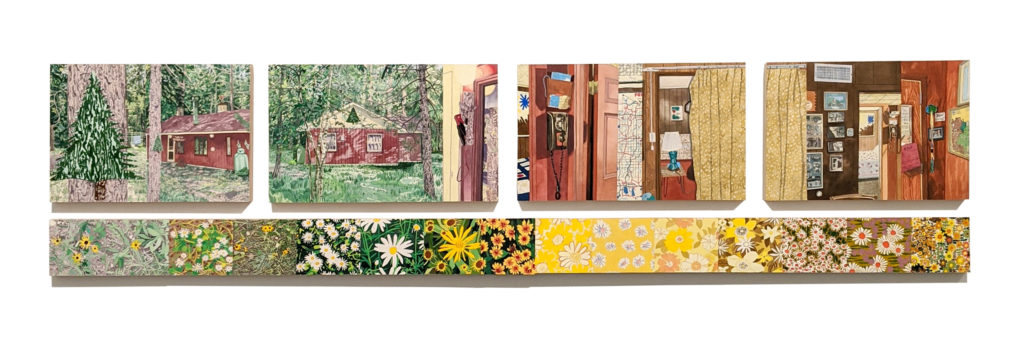

Juxtaposed with Koziol’s sculptures is Breehan James’s intricate composite painting of what appear to be scenes from a lost world. The Cottage (2020) documents her grandfather’s northern Wisconsin cabin and the patterns found in and around it. The multipanel painting depicts images of the exterior and interior of the cabin, as well as the attendant decorative motifs found within it. For James—a Scarborough-based painter, professor, and mother—the pandemic did not totally upend her studio practice: “I just started to wake up very early or stay up very late to get work done in the studio,” she says. Staying home and caring for her family, land, and art practice, James has become closer to the rhythms of daily life in a way that aligns with the survivalist aesthetic of the Biennial. Forced out of the grind of capitalism, artists focus back on the materials that build daily life.

Hector Nevarez Magaña, driving south, 2017, silver gelatin print. (photos courtesy of artist)

Hector Nevarez Magaña, she’s new here, 2020, silver gelatin print. (photos courtesy of artist)

Hector Nevarez Magaña, ofrenda, 2016, silver gelatin print. (photos courtesy of artist)

Hector Nevarez Magaña, by for a bit, 2016, silver gelatin print. (photos courtesy of artist)

The Bruce Brown Gallery opens up this hermetic world to one of surveillance, breakdown, and reconstruction. Elijah Ober’s work tracks a skunk on a night mission (with more clinical precision than skunk-tracking generally warrants), in a multimedia wall sculpture featuring video, light, and plaster footprint casts. Motion brings visual decay to photographic images, and photographers Mandy Lamb and Hector Nevarez Magaña take this as a narrative starting point in works that refer to impermanence. Lamb, who worked in the Arctic Circle, depicts seabirds in restless flight; Magaña’s work centers around images of motion-blurred landscapes, the interiors of vehicles, and fragmentary figures. “My work has always felt personal, almost journalistic or documentarian in the way that I am describing my world through near-truths,” Magaña says. “This pandemic presented an opportunity to examine the world within my literal, immedi- ate reach, and present findings on what near-truths exist there.” His black-and-white photographs, made between 2016 and 2020, are distorted by movement and atypical approaches to focus. They deliteralize the images’ status as records, and imbue them with a sense of transience. This proximity to fiction, and the attempt to reassemble the minutiae of daily life into narrative, informs the general sensibility of near-truth permeating this section of the Biennial. We reconstruct what we are given, sometimes making more out of our material, sometimes less.

Themes of rebuilding and reconstruction continue in the Main Gallery. Filled with light, the large room offers a sense of wandering among fallen monuments. Jeffrey Ackerman’s paintings and sculpture convey it directly, with their roiling narrative of a hedonistic culture in decline. In one of his paintings, satyrs prance past a dissipated princeling and his yellow-haired companion, as they drink and smoke in an intensely colorful palace; meanwhile, a smashed statue in the middle-ground is being attacked by vermin. The Main Gallery is dominated by a wall-size photo by Phil Lonergan that depicts the working artist’s hand; rising in front of this image, like gravestones or toadstools, is a pair of sculptural paintings by Henry Austin: A Death in the Family and Horseshoes (Where Are We Going?), both made in 2020. These works have parabola-shaped forms, emerging from tidy mounds of heaped-up gravel, with carefully illuminated stripes embedded among the stones. Sail-like and double-sided, the curved paintings’ compositions are abstract, dominated by hazy-edged pastel colors and sharply defined black shapes. The compositions feel familiar, recalling cave art and vaguely remembered dreams. Essentially symbolic, the two pieces also function as literal memorials—for Austin’s close friend Joe, who passed away in 2014, and for his father (also named Joe), who unexpectedly passed away shortly after the completion of these paintings. The work also memorializes what we have lost collectively and as individuals. Austin both recognizes that the monuments around him have fallen and takes their rebuilding as a natural next step.

Productive in the face of danger, artists rebuild from scraps to form the new world they dream of inhabiting. At the 2020 CMCA Biennial, we are given a number of possible answers to the question of how this rebuilding can be accomplished, and windows into the beauty that a world remade from fragments can contain.

The 2020 CMCA Biennial will run until May 2, 2021. A virtual tour of this exhibition, with links to ore work by all of the artists, can be found at the CMCA’s website.

Center for Maine Contemporary Art

21 Winter St., Rockland

207.701.5005

cmcanow.org