Abiding Sportsmanship

With a heritage dating back nearly two centuries, Maine’s sporting camps serve as stewards and guides of the state’s woods and waters

Former president Dwight D. Eisenhower fishes with a Maine guide in the 19 50s (photo courtesy of Liz Polkinghorn).

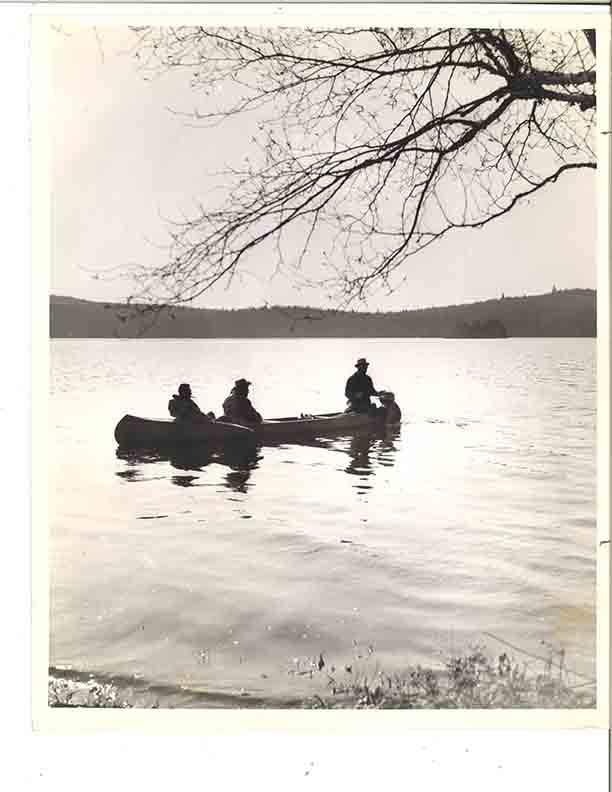

A sportsman receives a push off from a friend (photos courtesy of Liz Polkinghorn).

At once dangerous and serene, rugged and pacific, Maine is a complicated state, and is no stranger to contradictions and dichotomies. Its cultural and economic development has been colorful and varied, and often taxing, as the state has strived to cultivate and expand its urban centers, including Portland and Bangor, while also maintaining the last true wilderness in New England. Some of the most precarious businesses to withstand the ages and these changing tides have been traditional Maine sporting camps.

As early as the mid-1800s, when travel was largely by train or ship and before there were Yellowstone, Zion, and Yosemite National Parks, Maine gained a reputation as one of the choicest summer vacation destinations in America. Passenger trains ran north to Bangor, taking riders within striking distance of coastal summer resort towns such as Bar Harbor, Islesboro, and Camden. There the wealthy of the East Coast’s big cities could escape the crowds and heat, as well as the pollution from the booming Industrial Revolution. This influx boosted the local economies along the rugged coast, but for inland-dwelling folks, it was still a hardscrabble existence of farming and working the woods. For the lumberjacks, it was often a difficult life of toil and physical labor.

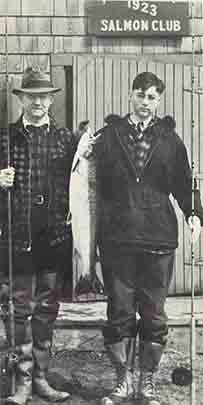

with their day’s catch.

The sporting camps that exist today evolved from those forestry and lumber camps. As word spread throughout the Atlantic states of world-class salmon and trout fishing, a few simple sporting camps popped up in the inland Belgrade and Rangeley Lakes regions, offering spartan amenities for rusticators. Stories of ten-pound landlocked salmon and of colorful Maine guides were told in men’s clubs and at water coolers from Scranton to Staten Island. Sport fishing enthusiasts who had been summering in the Catskills and the Adirondacks began making the journey to western and northern Maine. The original hunting and fishing camps were basic cabins with no running water, and employed outside privies for bathrooms. That weeded out all but the serious fishermen and, later, hunters. Sometimes, in those New York conversations, the decision of which sporting camp to stay in would come down to which one had the nicest outhouse.

Eventually, train lines expanded like tentacles throughout the state: north to the Acadian potato fields of Aroostook County and westward into the vast expanse of the North Woods to haul out lumber and logs. The railways brought opportunities. Sportsmen—and sometimes their scouts—rode the trains north to inquire about fishing and hunting camps. When in 1896 the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad tracks finally found their way to northern towns such as Masardis and Ashland and, within a decade, as far as Fort Kent, some locals saw an opportunity. Following the lead of the sporting lodges farther south in the Rangeley area, they opened their own, often using former lumber camps on lakes and rivers. It was a tough business. The camps were typically so remote that equipment such as beds, wood-stoves, and sinks had to be delivered by over-land freight and then canoe. Often food and everyday supplies required a whole-day trip to the nearest village or town and back. For some camps, it took two days.

As time moved on, Maine sporting camp owners began to feel the crunch of competition. Aviation opened up options all over the world for tourists, and the willingness to vacation in such austere conditions waned. Thirty years ago, facing competition, taxation, and rising operating costs, the owners came together to create the Maine Sporting Camp Association (MSCA). The MSCA has one unifying purpose: keeping the sporting tradition alive. With strength in numbers, the owners realized they could get group rates on continuously rising advertising prices and discounts on costly equipment, and even lobby for legislation.

Harvey Calden, president of the MSCA and owner of Tim Pond Camps in Eustis, speaks to one example of the challenges facing the industry: operating on leased land. “The insufficient protection afforded by leases has resulted in the disintegration of legendary locations,” he says. Camp owners also feel growing pressure to update the properties. There are many initiatives at the state level calling for expanded infrastructure for tourists in the North Maine Woods, but this investment is nearly impossible to justify with short-term leases.

A hunter waiting ready in position (photo courtesy of Liz Polkinghorn).

A fly fisherman prepared with a fly patch (photo by Peter Frank Edwards).

John Rust, president of the Maine Sporting Camp Heritage Foundation, echoes this sentiment: “Keeping up with things like running water in the cabins when some of these camps are still remote enough that it’s difficult to bring in a well drilling rig is very difficult. Making that financial commitment is especially challenging when you’re on a one-year lease with no guarantee seeing a return on your investment.” The rising value of waterfront in the 1990s made it more difficult to buy and operate sporting camps, which led to many of them becoming private compounds, shutting the public out, Rust says.

Some of the camps tackling these issues are new, not even 40 years old, but others have been around since Maine was a shiny new state. Tim Pond Camps in Eustis was built in 1832; the enduring Grand Lake Stream lodges, Weatherby’s Resort and Leen’s Lodge, have been popular with celebrities for decades; Bradford Camps near Ashland was established in 1890. In 2019 there were over 45 members of the association.

One of the oldest Piscataquis County sporting camps is Libby Camps, headquartered on the eastern shore of Millinocket Lake near the town of Masardis, on the fabled Route 11. It was founded by C.C. and Melissa Libby as a hotel in 1880, along the Aroostook River in the township of Oxbow. Unlike most turn-of-the-century sporting camps, the Libby Hotel was elegant, with good beds, bed warmers, gaslights, and running water. Over the next 40 years, the Libby family purchased camps and cabins throughout the area, eventually owning over 50 camps in three counties.

Today, Matt J. Libby owns ten cabins and the main lodge, where everyone gathers to eat on Millinocket Lake. The guides are based at the main lodge, as are the seaplanes that transport guests to remote trout ponds and lakes inaccessible by road. “In my great-grandfather’s day, it took several days to get here from Boston or New York, and people stayed for a month or two in the summer. A generation later, my dad booked [guests] for a week. Now it’s typically for three to four days.” Other changes are apparent to the business, he says. “Twenty-five years ago, there was very little bird hunting. Now that has really taken off. We can access better fishing spots now, because of the logging roads, that required canoes back in the day.”

Three men paddle away from shore on a Maine lake (photo courtesy of Liz Polkinghorn).

Hot coffee at Weatherby’s before heading out for the day (photo by Peter Frank Edwards).

In many ways, present-day sporting camps would be unrecognizable to a visitor from 1906. Over 100 years ago, the sporting camps were an extraction industry. Today, the fishing guides and camp owners are proponents of catch-and-release practices, and the hunting guides work closely with the game wardens. They are no longer filled only with hunters and fishermen; there are bird watchers, serenity seekers, cross-country skiers, photographers, and poets. Alden Camps offers tubing and waterskiing, while Eagle Lodge and Camps has a masseuse available for guests. Many lodges find themselves booked during the summer months as wedding venues.

Bradford Camps challenges visitors to disconnect and “E-tox,” and offers special organized events, such as the Sikorsky Aviation Seminar, Fiber Trek Wool Scouts Knitting Retreat hosted by Sarah Hunt, and Birders Weekend. “Twenty-five years ago we inherited a business that was largely traditional ‘hook and bullet,’” says owner Igor Sikorsky. “August was our quietest month. Fast-forward to now, and we’re not even open for deer hunting, in large part because there are fewer deer hunters and more family vacations.” It’s clear, however, that the core mission has stayed the same. Much like the sportsmen who met up year after year at the camps originally, “you get this wonderful synergy of three or four families coming the same week each summer,” Sikorsky says. “They met at Bradford Camps, and now go on other vacations together—some even have Thanksgiving together.”

While the experience might indeed look different than when the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad first tunneled through the rural wilderness in the 1800s, the present-day sporting camps of Maine still take their role as stewards of the state’s woods and waters very seriously. The owners, guides, and staff continue to showcase the state’s most wondrous resource—its outdoors—for those local and away, and are devoted to preserving nearly two centuries of heritage. With everyone that passes through, they leave an indelible impression that there is joy and serenity to be found in the Maine woods, should you seek it out.