Home Made

Soapmakers and ceramicists, jewelry designers and glassblowers, these artists represent a vibrant community of makers who are continuing Maine’s heritage of craft. Using materials ranging from neon tubing to lumber, their stories are told through the products they make and the people who invite them into their lives.

Michele Michael | Elephant Ceramics, Dresden

Michele Michael spent years working as a magazine editor and prop stylist in New York City—until 2010, when she took a class that changed everything. In a little pottery studio in Brooklyn, she found her true passion: working with clay to make porcelain and stoneware pieces. Since then, Michael has traded city life for rural, and she spends much of her time in a studio surrounded by pine and oak trees overlooking the Eastern River in Dresden. The founding owner of Elephant Ceramics, Michael creates one-of-a-kind functional tabletop wares, mostly serving dishes and vases. She starts and ends with an organic, simple form; each piece is hand-painted, and every batch of work is outfitted with a new, unique pattern. “No two pieces come out the same way,” she says. But one connective element emerges throughout her work. While each piece is uniquely its own, everything Michael creates is characterized by a shade of blue. “The color palette, patterns, smells, and sounds that come from the surrounding nature in Maine are a bottomless source of inspiration for me,” she says. Her strong connection with nature not only shapes her distinct color palette and penchant for blue; it also gives her a sense of well-being, which she hopes to reflect in her work. Maine’s coast influences everything she does.

Angela Adams | Angela Adams, Portland

Angela Adams’s eponymous home brand was born in 1998 when she and her husband, furniture designer Sherwood Hamill, braved uncertainty and set out to become full-time makers and designers. “We knew from the get-go that in order to be full-time designers and continue to live in Maine, where we both grew up, we would have to create jobs for ourselves here in Portland,” says Adams. At the time, Adams had been creating her own pattern designs and hand-painting them on walls, furniture, and other surfaces. Applying her unique patterns to area rugs felt logical, and once the Angela Adams brand was off and running with rugs and furniture, she expanded to other products such as bedding, fabrics, wallpaper, and home and life accessories. Her handcrafted contemporary pieces were met with immediate success, and her designs quickly became synonymous not only with her name but also with Maine design more broadly. She is often seen as a groundbreaker, and her enduring acclaim around the country and globe has helped elevate the local makers community as a whole. Adams says she is likewise indebted to Maine and its people for inspiration: “There’s so much beauty in the calloused hands and weathered faces that have endured short days and long winters; the fishing boats going out into sea smoke in the bitter cold; the farmers, knitters, net makers, and boatbuilders; the immigrant families that set up shops and bring traditions from other worlds to us. Maine is a constantly changing landscape and palette.”

Linda + John Meyers | Wary Meyers, Cumberland

Linda and John Meyers’s studio in Cumberland, adjacent to the house they share with their son, Fletcher, was once home to a hair salon called Judy’s Place. While any traces of hair dye or ammonia are long gone from the cutting-edge creative lab, the spirit of living and working in the same space has endured. “Coming from our apartment in New York City, it seems almost unbelievable that we can watch our son swimming in the backyard while we take calls or work on a new project in the studio,” Linda Meyers says. With a wink she adds, “We aspire to a very European way of business.” Their company, Wary Meyers, hand makes soaps, scented candles, and lip balms that can be found in over 200 stores all over the world, from Paris to Los Angeles. The pair conceives of all the whimsical scents themselves, and each item is hand-poured and packaged in small batches. Linda and John’s inspiration is myriad, ranging from the midcentury modern style and 1970s Pop Art (that’s on impeccable display in their Cumberland home) to vintage Hollywood to their backyard swimming pool, and to Maine itself. They bring these influences to life in splashy typography and packaging; in the vibrant stripes that color their soaps; and in aromatic concoctions such as Forest Primeval, Xanadu, and Mainely Manly. “Coming from a city like New York, no one has a bigger appreciation for this state than us,” says Linda, “We would never have been able to create what we have or scale the way we have anywhere else.” Echoes John: “Maine has given us the room to create.”

Terrill Waldman + Charlie Jenkins | Tandem Glass, Dresden

Charlie Jenkins and Terrill Waldman, glass-blowers for over 30 years, were sharing a studio in Oakland, California, in 2006 when they decided to move to Maine to buy their own space in which to live and work—nearly impossible to do in the East Bay, at the north end of Silicon Valley. After arriving in Dresden, they started Tandem Glass, a hand-blown glass studio that produces handmade objects both sculptural and functional. They’re widely recognized for their richly saturated colors and intricate designs. Of their signature vivid palette, Waldman says, “I think of color as my material. Our unique glass color is created in very small, limited batches. Some of the materials we’ve used are available in such tiny quantities that we’ve actually lost access to some of our favorite colors over the years.” Individuality is at the core of their ethos. No one piece they make is ever exactly replicated, from mixed-material mosaic glasses to charismatic pink and white speckled pigs, and each is intended to be interpreted differently by everyone who sees them. Jenkins emphasizes the importance of “the natural world and the color and light resonating from it.” They utilize as many natural resources as possible from their midcoast home base: cherrywood, cork, iron, and bronze help form the shapes. Beeswax prevents the tools from scratching the glass. The pair are advocates for the maker community within the state, with Jenkins having served as the president of the Maine Crafts Guild and Waldman on the board of the Maine Crafts Association. They give back with their annual FUNdraiser that typically benefits the Maine Crafts Association and the Good Shepherd Food Bank.

Jeremy Frey | Jeremy Frey Baskets, Eddington

“The thing I love most about what I do,” says Passamaquoddy basket weaver Jeremy Frey, “is starting from nothing.” When he was 20 years old, Frey’s mother taught him how to gather materials from the woods, cut them, shape them, and design their final forms. What begins as black ash, sweetgrass, cedar bark, birch bark, and spruce root becomes an intricate, detailed basket by the end of Frey’s process. In all, it takes about a month and a half to complete a large basket, but Frey says he’s sometimes spent up to six months on a piece. “It’s a meditation,” he says. “It always has been.” The tradition of basket making is deeply rooted in the history of the region’s Wabanaki people. Frey weaves a particular type of basket called a fancy basket, which is made for indoor use and display, as opposed to the Wabanaki baskets of centuries ago, which were often used during potato harvests. When Frey started to learn the tradition, the only baskets still being woven were for utilitarian purposes. “If you think about fancy baskets,” says Frey, “they have evolved because there’s a culture in Maine that encouraged that and embraced that.” Frey’s practice of the ancient art form requires substantial foresight. It can take weeks to prepare a braid and up to two days to split an ash log into fine ribbons. When so much time is invested in preparing a design, it’s imperative that the final product weave together seamlessly.

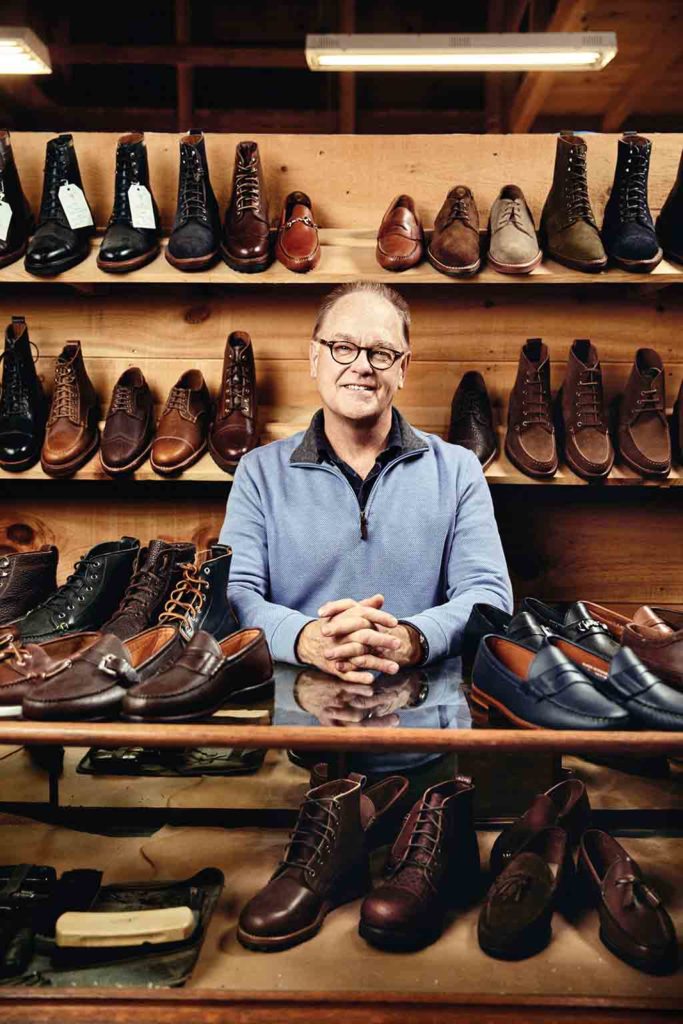

Mike Rancourt | Rancourt + Company, Lewiston

As a high schooler, Mike Rancourt did odd jobs at his father’s handsewn shoe factory in Lewiston, and remembers being mesmerized by the hand-stitchers making moccasins. At the time he didn’t expect to end up in the shoemaking industry like his father. “I remember the first time I saw a pair of calfskin loafers from Cole Haan—they had been made by a factory in Bangor—I was amazed that that kind of beauty existed in making a pair of shoes,” he says. In 1982 Rancourt and his father, David, founded Down East Casual Footwear, which made moccasins, boat shoes, and slippers. Its biggest customer, Cole Haan, later bought the company. Rancourt started another company, Maine Shoe Company, that he eventually sold to Allen Edmonds. He worked for the shoemaker for 13 years, but when Allen Edmonds decided to shut down the Lewiston factory, Rancourt and his son, Kyle, bought the business back and launched Rancourt and Company in 2009. The company produces around 400 pairs of handmade shoes and boots a week for companies such as Ralph Lauren and Sperry and its own label, ranging from hand-stitched moc-style shoes like the ones Rancourt’s father made decades earlier to boots to minimalist sneakers. A few of the hand-stitchers were even trained by Rancourt’s father in the ’80s. “We still last by hand. We still punch by hand,” Rancourt says. “We’re still doing it the same way it’s been done for over 100 years.”

Edith Armstrong | Folia, Portland

When Edith Armstrong graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design with a degree in jewelry and metalsmithing, knowing that she wanted to work for herself, she designed a pair of brass leaf-shaped earrings and pitched them to various local boutiques. She used the encouraging feedback she received as a catalyst for her craft. Raised outside of Boston, Armstrong spent her summers in Maine. “My heart is in Friendship,” she says, referring to the coastal town she and her family still escape to as much as possible. In 1993 she took over a shop on Portland’s Exchange Street, which became Folia. Her store is a showcase for several proprietary lines, including Air-Frames, where Armstrong’s signature 18-karat green gold moors sparkling diamond beads; the Gemstone Collection, precious stones framed in the same gold; and the Flora Fauna Collection, which harkens back to her early days as a postgrad, using nature and its many incarnations as inspiration for each piece. Armstrong is also known for her custom work and the relationships she’s forged over the past three decades. “I’m frequently seeing people whose wedding rings I designed come in for their own children’s rings,” she says. These bespoke designs have frequently been fonts of inspiration in their own right. “A woman came in once who was scrapping an old medallion bracelet, almost Turkish looking, that she didn’t want anymore.” Captured by the textured, somewhat baroque patterns, Armstrong developed her Cesca line, an enduring favorite at the Exchange Street store. Armstrong is a prolific patron of charitable causes. She is devoted to several local philanthropic organizations, and her pieces are frequently auctioned throughout the state to raise funds for the people and institutions of Maine.

Julie Morringello | Modernmaine, Stonington

“I’m obsessed with materials,” says designer Julie Morringello. Trained as a furniture maker and an industrial designer, she worked in both fields for some time before founding Modernmaine, a company that specializes in modern, artist-made light fixtures. By cutting, bending, and shaping wood, Morringello creates contemporary, sculptural lighting for residential and commercial use. Some processes require digital as well as manual fabrication techniques, but every piece of lighting’s final form is hand assembled by Morringello in her Stonington studio. She mainly works with laser-cut maple veneer, using paper maquettes to help with design concepts and processes. Wood is her preferred medium, but she has worked with a variety of materials ranging from paper and acrylic to Tyvek and fabric. Morringello is Modernmaine’s sole artist, and she often finds inspiration in emotions and expressions. “An entirely new piece might be inspired by something I’ve seen or experienced,” she says. “I think about things like connections, cultural references, light, color, and so on.” For Morringello, inspiration can be as simple as a gesture, a reflection, or a certain material or space. Emotive perceptions are then merged with practical concerns, such as function, hardware, and the manufacturing process. It’s this intersection of competing ideas that Morringello finds most exciting—it’s the part of the creative process that, she says, “acts as a kind of combustion that fuels the rest of the project.”

David Johansen | Neon Dave, Portland

Like many artists, David Johansen starts with a sketch. Using a torch, Johansen bends glass tubes, cutting and welding them together as needed to match the shape of his sketch. Once a piece is complete, he’ll create a vacuum and add an inert gas, like neon or argon, that illuminates when electricity is run through it. The light’s color depends on both the gas and the powder coating on the inside of the tube. Johansen plays with different combinations to create his colors, which he then manipulates further by placing tubes of differing colors next to each other. “You see right here is the whole world I work in,” Johansen says as he points to the space where light from an orange-hued tube and a purple tube meet on the backdrop of a piece. Although Johansen’s neon signs can be found around Portland, such as the neon scorpion at Downtown Lounge and the “Live Nerds” sign at Arcadia National Bar, he’s primarily an artist. “I like art that has got a lot of craftsmanship to it,” Johansen says. “I’m not a sign guy who started making art. I’m an art guy who started making neon and has made a few signs.” He says a challenge of working with neon as an artist is that, because the medium is so often associated with signs, it can be hard to see it as art. “I’m always trying to think of what has never been done,” Johansen says.

Adam Rogers | Adam Rogers Studio, Portland

Adam Rogers already had a career in corporate architecture when he decided to try his hand at woodworking. At age 28 he enrolled in a furniture design graduate program at the Rochester Institute of Technology’s School for American Crafts and spent the first semester working only with hand tools. “After that, I was hooked,” Rogers says. To turn his passion into a career, he took an entry-level custom design job at Thos. Moser in Auburn, where he learned how to scale expert craftsmanship without losing quality. “The idea of making a one-off art piece is less interesting to me,” he says. “The value of this process is the end result.” He eventually worked his way up to director of design and product development at Thos. Moser and was responsible for designing all of the furniture. After more than seven years at the company, Rogers left to become a full-time professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology and pursue another of his passions: passing on his knowledge of fine woodworking. “It’s a tradition that relies on the sharing by other people. It’s ultimately the only way it survives,” he says. After two years, Rogers returned to Maine and launched his furniture design studio, where he does work for a variety of clients, including Chilton and Radnor, and he continues to teach at other schools. With his furniture, Rogers lets craft inform the design. He tries to incorporate evidence of craft that emphasizes the transition between two pieces of wood, such as exposed pinned joints where a dining table’s legs meet the apron below the tabletop and shaped transitions at the top of a chair’s leg joinery. “In really simple but definitive terms, I think design is deciding what to turn a tree into, and craft is turning it into that,” Rogers says. “It’s that simple.”