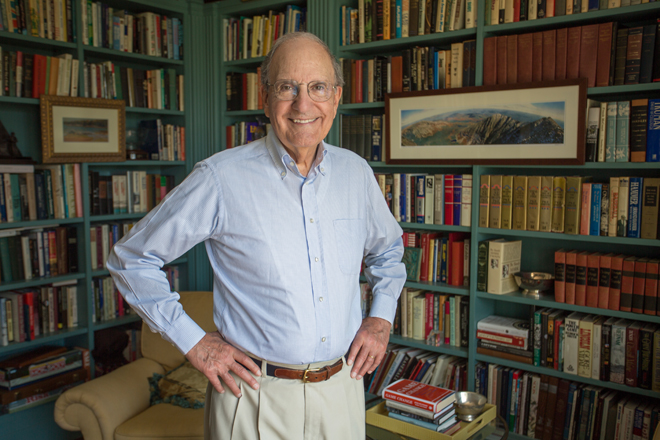

Senator George Mitchell

PROFILE-September2013

By Jaed Coffin

Photographs by Jack Montgomery

The Debts Shall Be Paid: Senator George Mitchell and the help along the way

Senator George Mitchell, two months from his eightieth birthday with not much more than a night’s sleep since returning from Washington, D.C., sat in an armchair in his study at his home in Seal Harbor wearing a button-down shirt, khakis, and running shoes. It was a Tuesday during the last week of June, nearly 11 in the morning, and the world outside was hazy and humid and overgrown and green. The senator told me we had “about an hour” to talk; that afternoon, he said, he would board a return flight to D.C., to chair a bipartisan think-tank committee meeting with Senator Olympia Snowe about safety regulations for American retailers’ factories in Bangladesh. Later that week, he was headed to the Aspen Ideas Festival to give a lecture about the Middle East, and then he was off to State College, Pennsylvania, to serve as Athletics Integrity Monitor at Penn State. And yet in spite of his attention to these present matters, and regardless of the presidents and prime ministers and fellow senators and major league baseball players and global leaders who, over the last 50 years, had worked alongside the senator to address matters of grand scale, the topic that Senator Mitchell wanted to talk about first was his high-school English teacher who, 65 years ago, changed his life.

“Her name was Elvira Whitten,” Senator Mitchell said. “She had perfect posture. Perfect.” He circled his finger over his head as if drawing a halo. “She had elderly gray hair she wore swept up in a bun on her head. Everyone loved her.”

Perhaps you’ve heard the tale of Elvira Whitten before. The senator has been telling the story for almost two decades. He told it to members of Congress in 1994, as he announced his decision not to run for reelection; he has told it to auditoriums full of college students across the country; he has told it to entire classes of Maine high-school seniors during a 12-year period when he vowed to speak at every graduation at every high school in the state—once giving three addresses in a single day.

The year was 1948. The senator was 15 years old, a junior at Waterville High School, a quiet pupil in Elvira Whitten’s English class. At the time, Senator Mitchell considered himself an “insecure” and “uncertain” student. The fourth of five children, Senator Mitchell was the youngest of four brothers—all renowned college basketball players. His father, George Sr., an Irish immigrant adopted by a Lebanese couple from Bangor, worked as a laborer at Central Maine Power. His mother, a Lebanese woman who came to the United States at the age of 18, worked the night shift in the local textile mill.

One day Elvira Whitten asked Mitchell to stay after class. “My first thought was that I wondered what I’d done wrong,” Mitchell recalls. Elvira Whitten asked him, “What do you read?” The senator was too embarrassed to tell her that the only thing he read was comic books. Elvira Whitten handed him a small novel. “I think you should read this,” she said.

That evening, Mitchell began reading The Moon Is Down, a novella by John Steinbeck about the occupation of an unnamed Scandinavian town by an unnamed empire led by an invisible presence simply called The Leader. It is a story about World War II, clearly—Steinbeck published the book in 1942 as part of an Allied counter-propaganda effort—but it is also a story about the endurance and courage of the human spirit. The Moon Is Down is not a light read for anyone, never mind a 15-year-old high-school boy: there are executions and betrayals, murders and seductions, fear and useless violence; the line between good and evil, for Steinbeck, is a precarious one.

Senator Mitchell stayed up all night reading the novella, and in the morning, when Elvira Whitten asked him what he thought of the book, Senator Mitchell’s “analysis was probably longer than the book itself.” When he returned her copy of The Moon Is Down, she handed him a new novel to read: Parnassus on Wheels, a novel written by Christopher Morley in 1917 about a woman who lives on a farm and who, cynical about her brother’s recent fame as an author, blows her life savings on a horse-pulled library-cart. It is a story about education, and the value of reading and literature, and the first line reads: “I wonder if there isn’t a lot of bunkum in higher education?”

For the rest of that year, Elvira Whitten gave Mitchell more books to read. On the last day of the school year, he asked her what he should read next. “You get to pick your own now,” Elvira Whitten told him. His first choice: Men Against the Sea, the second book in the Bounty Trilogy. (The first book of the trilogy is the classic Mutiny on the Bounty.) “That,” Mitchell recalls, “was the first summer that baseball had any competition.”

Despite Elvira Whitten’s urgings, Mitchell breezed through his senior year without much idea of what he would do after high school. His father, a man who was fluent in both French and Arabic and who had worked tirelessly his entire life, had recently lost his job at Central Maine Power. Although Mitchell worked for his brother as a janitor at the Boys and Girls Club and at the employment office, and sometimes ran a cotton candy machine at state fairs, it wasn’t enough to pay college tuition. His older brothers had gone to school on basketball scholarships, but Mitchell didn’t have that kind of game.

And then one day a manager at CMP named Hervey Fogg called Mitchell into his office and asked him what he planned on doing with his life. “You know my father’s out of work?” Mitchell said. Fogg knew as much, but then told Mitchell about a friend of his named Bill Shaw, who worked in admissions at a small college forty miles south. “I’d like you to go there,” Fogg told him. He handed him a sheaf of papers: Mitchell’s high school transcript. “Take these with you,” he said.

Mitchell’s family didn’t own a car, so on the morning of his interview, his mother packed him a paper bag full of sandwiches and Mitchell walked down to the highway to begin hitchhiking south. The trip only took an hour, but, worried he’d be late, he left five hours early. “I got picked up by the first car,” Mitchell recalls, which left him with four hours to kick around campus. When he met with Bill Shaw, Shaw asked him, “Are you willing to work while you’re here?” One of the many jobs the senator held as a student was working for Brunswick Coal and Lumber. His first day, he was told to drive a truck to Thomaston, fill it with 90-pound bags of cement, and drive it back to Brunswick. “I’d never even driven a truck before,” Mitchell says. “And I’d only driven a car once.”

This story of how Mitchell found his way to Bowdoin is, like the Elvira Whitten story, a tale that Mitchell has told and retold, such that it has become one of the founding myths of contemporary Maine culture, a Johnny Appleseed fable of education. I recently asked some of my buddies from Brunswick if they remembered the story, perhaps from a Maine studies course in junior high. “Yeah,” one of them said. “Didn’t he, like, walk to Bowdoin from Waterville with a quarter in his pocket or something?” Good enough.

Over the next four decades, Mitchell’s life evolved in ways that he still believes were “entirely accidental.” He served in the Army for two years after college, and earned his law degree from Georgetown in 1961. He served as an assistant to senator Edmund Muskie, ran for governor, was appointed U.S. Attorney for the District of Maine by President Carter, served as a federal judge, and in 1980 was appointed senator for Maine by Governor Joseph Brennan following Senator Muskie’s retirement. While in Washington, Senator Mitchell quickly earned the confidence of his follow senators, and ultimately became senate majority leader in 1989. In 1994, he refused an appointment by President Clinton to become a justice in the Supreme Court. Instead, Mitchell became active in the global mediation and conflict resolution efforts that he is perhaps best known for. Under President Clinton he served as special envoy to Northern Ireland, and later led a peacemaking resolution between Israel and Palestine. He has served as chairman of corporate boards from Disney and Pixar to the Boston Red Sox, overseen an investigation into Major League Baseball’s steroids scandal, and been appointed by President Obama as special envoy to the Middle East.

Despite Mitchell’s decorated political career, it’s almost reflexive in this day and age to be a little bit cynical about all politicians, no matter how good their stories are. Mitchell’s career and personal life have not been immune to media speculation: his connection to the Boston Red Sox was a hot topic for journalists during the steroids investigation, as as was his engagement to his current wife, Heather Maclachlan, a well-known sports marketing agent. But as a politician, Mitchell has earned the rare right of privacy for his personal affairs. As we talked Maclachlan was doing yoga in the other room, appearing only briefly to borrow Mitchell’s cell phone. Evidence of his two children, 15 and 12, was in the well-used baseball pitchback net in the driveway.

Even in the presence of a man of such stature and reputation, it is possible, and, I suppose, fair, to look between the lines of his inspirational stories for the story which exists between them. The senator recalled that his father was “very despondent when he was out of work. It was very, very tough on him.” When he mentioned that his mother was a “very skilled weaver” who “spent her whole life in the textile mills, 40 years,” his tone turned somber. When I ask him about his connection to his past—born in 1933, Mitchell entered an America crippled by the Great Depression, a Maine where manufacturing industry was reduced by 50 percent—he morosely admits that the mills where his parents and his community once worked are “all gone now…all gone.” When I ask him about his experience growing up in an ethnically diverse family, and whether he grew up speaking Arabic, he pauses before saying, “For my father, it was all about assimilation.” I know from my own experience as the son of an immigrant that such a journey to America, even as a second-generation child, is not a simple one, or one that is always happy, even in hindsight. Attending an institution like Bowdoin College and delivering oil or shoveling driveways while other students are not, is an experience not exempt from some natural bitterness or resentment, some sense of injustice or envy.

When I entered his home through a screen door, to the hopeful music of Aaron Copland trilling from an invisible source, a blonde poodle wandering through a living room, past a mantle adorned with tennis trophies, Senator Mitchell asked me about my story, and my family, and so I told him: my mother is from a village in Thailand, my father was a soldier in the Vietnam War; they married in Thailand and came back to America together. After their separation, my mother, a nurse who worked the night shift at the local hospital, and my sister and I lived in an unfinished apartment on Federal Street in Brunswick. Over the course of just two decades, though, we moved into a house near the college neighborhoods, and my parents sent both my sister and me to college. Now, I told him, I teach part-time at his alma mater, which is across the street from where I live. Mitchell nodded vigorously. “That’s America,” he said, his voice rising, his eyes more alive and awake than they had been all morning. “It’s the first true meritocracy.” Then he paused. “And yet it’s not a true meritocracy, but it’s one of the few countries where this is a universally recognized ideal.” He cited a book by the historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. called The Cycles of American History.“Schlesinger would say that right now America is in a period of rapid digestion and absorption. But it’s very compressed.” What used to take generations to accomplish—sending a child from a working class background to college—“can now be done in 20 years.” And sitting there in his study—the walls lined with hundreds of books—in a town inhabited by Rockefellers and celebrities such as Martha Stewart, I have to ask him how he is able to maintain a connection to his past. The old mills are long gone, and he is, he says, the only one of his family who doesn’t live in Waterville. “It’s very difficult,” he says. “Very difficult. The real danger is what you will give to your kids. Finding restraint when you want to give them everything is the most difficult part of being a parent.”

Now the hour was nearly up. Shaded from the daylight outside, you could see the Lebanese in Mitchell’s face, you could see the 80 years of life he has lived and, though he looked well-rested and presented the same preternatural calm that he is known for, I had to imagine that he was feeling a bit tested by his imminent departure back to the place where, for so much of his life, he has done his work.

“One of the few regrets I have in life,” Mitchell told me, “is that I never thanked Mrs. Whitten.” One way he tried to settle his debt of gratitude to his former teacher came during a fundraiser for the Mitchell Institute—a nonprofit that he started nearly 20 years ago to raise scholarship money to help low-income Maine students pay for college. The year was 1994, and Senator Mitchell was on the verge of reelection to the Senate. In anticipation of his campaign, he’d raised two million dollars—a pittance by today’s standards. After he publicly announced that he would not seek reelection, he told his donors that they could either have their money back or contribute to the future of his Mitchell Scholars. Fifty percent chose to donate to the Mitchell Institute which has since raised over 10 million dollars to send Maine kids to college.

Later that day, I looked over some notes I’d made about the books in Senator Mitchell’s study—Game Change, a book about the 2008 presidential election, had been on the table between us. Way up on a high shelf near the ceiling was a book called Lebanese American Relations. At eye level: The Life of Mohammed. On the floor, on top of a stack of books, was a novel called Mr. G, by the physicist Alan Lightman, about the creation of the universe from the perspective of God. Close enough to touch had been a multivolume history on the United States by the scholar Page Smith. I didn’t see any tattered copies of Men Against the Sea, or Parnassus on Wheels, or even The Moon Is Down. But in the following days I read Steinbeck’s novella just as the senator had 65 years ago—in one sitting, start to finish, in the middle of the night. In the final chapter of the book, as the occupying forces lose their grip on the war, the mayor of the town, an honorable man facing his own execution, begins to quote and misquote Socrates’ final words—heavy stuff for a 15-year-old boy from Waterville to consider, heavy stuff for me on a summer day. The mayor, mimicking his Greek model, asks his friend to settle his debts with Asclepius, the god of healing. There are a million ways to interpret Socrates’ final moment—a cosmic promise of the afterlife, an appeal to understanding death as merely a physical event—but the final words of the mayor’s friend seemed to rise out of context and apply more to Senator Mitchell and the work he has done in his life, and to Elvira Whitten, the teacher who made sure he kept reading.

The final line of The Moon Is Down reads: “The debts shall be paid.”

And here, I cannot help but imagine George Mitchell as a young man, closing the book, turning out his light, waiting for sleep.