Shifting Dynamics Through the Power of Theater

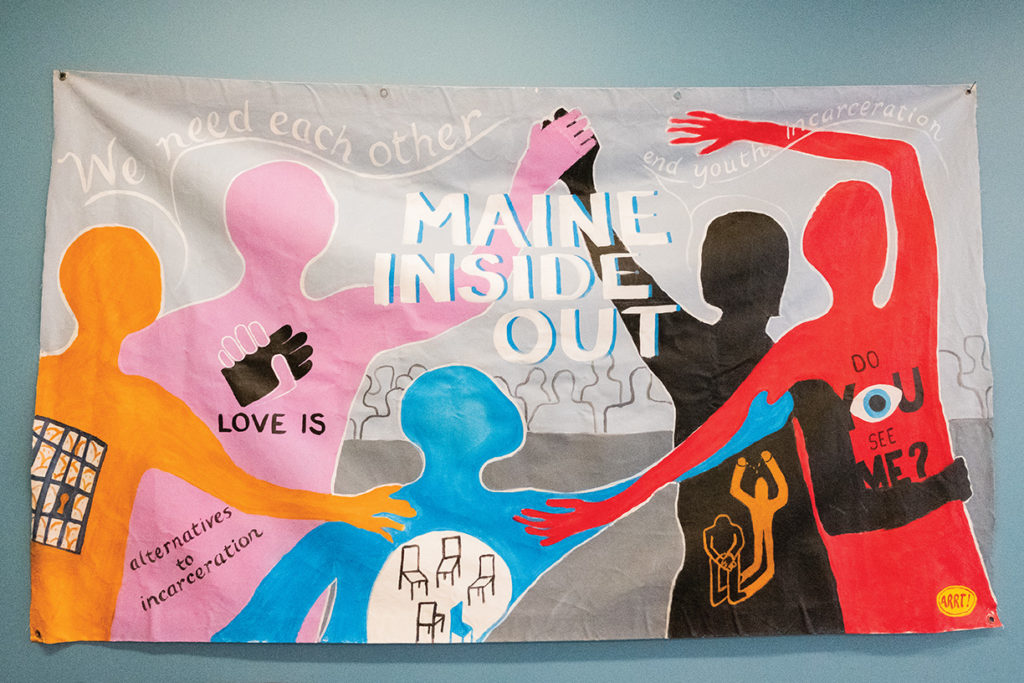

Maine Inside Out uses improvisational theater to help both youth and prison communities share their experiences and make an impact.

Shifting Dynamics Through the Power of Theater

Maine Inside Out uses improvisational theater to help both youth and prison communities share their experiences and make an impact.

by Katherine Gaudet

Photography by Jennifer Hoffer

Issue: October 2022

On the stage of the auditorium at Lewiston Middle School (LMS), seventh graders are becoming statues. A girl in a hoodie winds up a punch while a boy in another hoodie crouches, hands spread to cover his face. A girl in a headscarf cups her hands around her mouth as if calling for help. They are telling their middle-school stories with their bodies, and with each other.

The students are participating in a program led by Maine Inside Out (MIO), an organization with a long history of creating dramatic performances along with incarcerated people. In recent years the organization has been doing more work in the community, collaborating with formerly incarcerated people to share and process their experiences and advocate for change in the justice system. The LMS program is a new venture. “Middle school is where kids start to ask all the questions: they start saying, ‘What is it that I’m missing?’” says facilitator Adan Abdikadir, who attended LMS himself. “They’re not the way they were raised anymore; they’re their own person.” Noah Bragg, another facilitator, explains that the idea came from some of their incarcerated participants. “We heard many stories of people getting system-involved in middle school. They would say, ‘This is a point when life really changed. I wish I had Maine Inside Out then.’”

Middle schoolers can be a challenging audience, but Maine Inside Out is used to working through challenges. They recruited participants by performing a seven-minute scene during a school assembly in March. More than 70 students signed up, and from that pool LMS faculty selected a group of 26. “There was something about seeing this very simple but strong scene around a middle-school experience, knowing actors had created it themselves, that drew the students in,” says MIO cofounder Chiara Liberatore. “Whatever it is about our theater spoke to the students. They saw the scene once, and they still will refer back to it. What that says to me is that they want this format to tell their own stories, and to work through what they are experiencing together.”

Lewiston Middle School student actor Stacy Bontogo with MIO cofounder Chiara Liberatore.

Unlike most of the plays performed on school stages, Maine Inside Out productions don’t come with a script. They are created by the actors, through a process that encourages participants to seek not only the expression but also the root of their experiences. On the wall of MIO’s Lisbon Street office, a drawing of an iceberg on an oversized Post-it illustrates the group’s process. At the top are issues the students have identified in their school: bullying, bystander behavior, targeting, snitching, and so on. Below the surface of the water are two more layers: the structures that create the patterns and, at the bottom of the iceberg, the beliefs—sometimes unrecognized, often complex—from which the problems grow.

Working through those layers with seventh graders isn’t easy, says Liberatore, but with continuous, gentle encouragement, they eventually deepen their thinking. The LMS students describe structures ranging from xenophobia and poverty to teenage hormones, resting on beliefs that include “fear of standing up,” powerlessness, homophobia, and the concept that some people are “bad apples.” All of this informs the creation of their early June performance—itself the small tip of a much larger process full of experimentation, practice, and reflection.

Twice a week, for an hour at a time, five facilitators—Abdikadir, Bragg, Liberatore, Tyler Jackson, and Darryl Shepherd, Jr.—divide themselves between two groups of students, working on scenes to be performed for parents and friends. There’s lots of creativity, but progress is slow. A few weeks before the performance date, the show hasn’t yet cohered. The students come up with scenes, but instead of building on them in subsequent sessions, they tend to drop their former ideas and start over. And not everyone stays involved. A student refuses to put away his (prohibited) phone, and a teacher is called in. “There’s a long list of students who wanted to get into this program,” she tells him. “You need to decide. Do you want to be here, or do you not want to be here?” He chooses to leave, and she escorts him out of the room. The facilitators regroup the rest of the students and keep working until the end of the period.

Back in their Lisbon Street headquarters, the group settles in to share highs and lows of the day. The incident with the student on his phone is troubling Bragg. It had been a hard moment, but afterward the students had done better work. For the first time, a student had returned to a previous scene, exclaiming, “I know what happens next!” Bragg and Abdikadir make a plan to follow up with the student who left the group (he would later return, freshly committed to the performance). The conversation continues to a discussion of structure and freedom: how can the facilitators provide enough of a “container” to help students stay focused while leaving space for them to make their own choices?

This is an important problem for an organization with freedom at the root of its mission. The organization started small, when Liberatore moved to Maine and met Margot Fine and Tessy Seward, who shared Liberatore’s commitment to creating change in the prison system through the arts. Their first project together came to life in 2008, when they worked with residents at the Women’s Reentry Center in Bangor to create an original production. They were able to gain the necessary approvals to hold the performance off-site, at the University of Maine’s Black Box Theater, for an invited audience. “It was really solidifying for us as a team,” says Liberatore, and the three committed to growing the organization. At first they had no budget; they sought grants and fiscal sponsorships to cover snacks and travel. All three had other jobs and were new parents, so progress was slow but it continued. A contract with Long Creek Youth Development Center put youth programming at the center of their work for several years. In 2013 they held a series of events titled “Culture of Punishment: From Parenting to Prisons,” including an original work by seven residents of Long Creek. Sister Helen Prejean, author of Dead Man Walking, was a keynote speaker. The events attracted press attention and accelerated the organization’s growth. In 2014 MIO was organized as a nonprofit, and in 2015 Liberatore, Fine, and Seward became its first employees. Today there are 12, 8 of which are people with a lived experience of incarceration.

MIO’s slow, determined growth has brought changes: more stability, more recognition, and an evolution of their message and mission. “As we grew, and the young people grew in their experience and their artistry, the message got a lot bolder,” says Liberatore. “When the participants reentered the community, they had more opportunities to share their experiences from prison, their traumas.” The group’s philosophy is rooted in what the Brazilian playwright Augusto Boal named the “theater of the oppressed,” in turn influenced by the methods of educator Paolo Freire. At the heart of this model is a shift from authoritarian power structures to collaborative understanding—from monologue to dialogue. “We’re creating theater to find out what communities need, for prisons not to exist,” explains Bragg. “We’re using theater to balance out power dynamics, so we can have a real conversation about how to change those structures.”

MIO’s mission now incorporates work both inside and outside of prison communities. The group facilitates projects in which people can work through their experiences with incarceration while sharing those experiences with the larger public. This summer, they launched a new project inside Mountain View Correctional Facility in Penobscot County, and have begun the process of creation and reflection that will build into a new performance over several months. In the fall they will begin hosting public events at their recently opened Lewiston community site. And they’ll be returning to LMS to continue working with the same students as they move into eighth grade. “I have a vision that we will be in every prison in Maine, and some jails, some group homes,” says Liberatore. “Our vision is to be in the communities where the most people have been impacted by incarceration: Lewiston, Waterville, Biddeford, Portland. We want to have teams of facilitators who are from those communities.”

gathered in front of the Kennedy Park bandstand in Lewiston for a final circle to share thoughts, feelings, and fellowship.

Many people who spend time with the prison system—whether as residents, employees, or interested citizens—find hope hard to maintain. To continue to work for change over years and through difficulties takes patience, care, and an unshakeable belief in humanity. “I want people to feel in their hearts how we’re all impacted if someone’s incarcerated,” says Liberatore. “Unless you’ve been incarcerated yourself, or spent time with someone who has been, you don’t really know how that feels. Being touched by an artwork can give people a way to share in that experience. Maybe it’s a little cliché, but no one is free until we are all free. I want people to feel that in their body and their heart, so that they will join a movement to change things. It won’t work if it’s just some of us. We need everybody.”

READ MORE:

- Claiming Space at the Table

- How to Go Antiquing Like a Mainer

- Four Young Writers to Watch in the Pine Tree State

- Milkweed Man

- A Stitch in Time