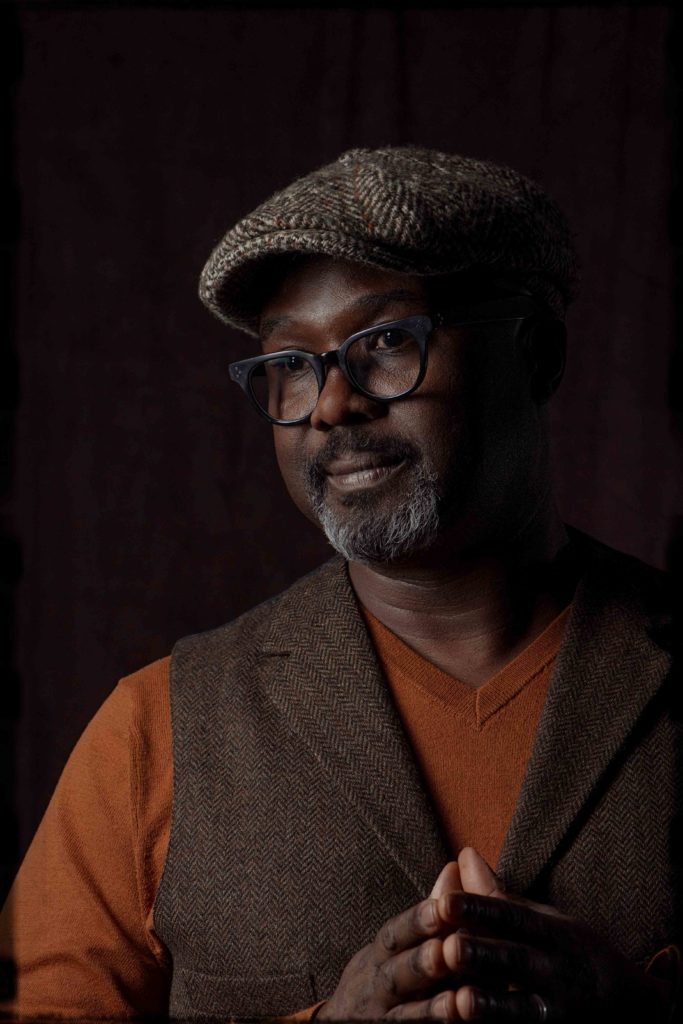

Through His Lens

A master of portraiture, Séan Alonzo Harris uses photography to ask questions about race, gentrification, and who makes up the communities around us

Séan Alonzo Harris, a fine art, commercial, and editorial photographer, is known for his arresting environmental portraits and for capturing often-overlooked populations. After living in Portland for nearly 25 years, Harris recently moved to Waterville, where he photographed and exhibited I Am Not a Stranger, a series of 58 portraits of Waterville community members that was shown at the Colby College Museum of Art in late 2019. Another project, Visual Tensions, paired portraits of Portland Police Department officers and people of color. It took Harris three years to complete Visual Tensions, and during that time Harris also photographed immigrants from Africa playing on the basketball courts of the Kennedy Park housing project in Portland’s East Bayside. Those images help make up his Voices in Our Midst series, which was shown at the now-closed PhoPa Gallery and includes three photos that were chosen for the Portland Museum of Art’s 2018 Biennial. This spring as an artist-in-residence at Indigo Arts Alliance, also in East Bayside, Harris continued to add to his Voices in Our Midst collection by documenting the neighborhood around Kennedy Park and taking studio portraits of its residents. Harris plans to exhibit that work at the neighborhood’s Cove Street Arts in December.

What are you trying to do when you take a portrait of someone?

In Voices in Our Midst, it is all about Kennedy Park. I don’t know if you know that area at all, but it’s been super gentrified. You have low-income housing, and then you have million-dollar condos. They’re right next to each other right now. I believe in ten years that whole thing is going to be ripped down. The people who live there today are not going to be living there tomorrow. Before it was Irish and Italians who were living there, and now we have Africans, Arabs, and some other races that are mixed in. But it looks completely different, and if you look at those photographs, you would not say, “That’s Portland,” just because of the makeup of who lives in Portland, but that is Portland. What does that mean to the people who are in these pictures? What does that mean to the people who are viewing these pictures? What does it mean for the area that they’re living in, that might go away? How does one grapple with all of those things? They’re new to the area, and it’s obviously a different climate; it snows here. These are African, dark African people, and what does all that mean? I don’t want to use the word assimilate, but how do they make their way with where they live now? What do they do to survive? Those are just questions about humans and humanity.

Is that what you want people to take from this series? Some sort of deeper understanding of humanity or their community around them?

Well, I think that it depends on the person, because those questions I just posed, not everyone’s going to take those away. Some people are going to go, “Wow, great photograph. I like it.” Other people might be a little bit more curious about it, but we’re also living in the age of Instagram, and they’re not looking at images in the same way as they used to. It’s a learned thing where you go to a gallery and you sit with an image and you go back and back and back and truly try to dissect a body of work or a piece of work. That’s what I’m trying to do, but it’s really up to the audience to take it away. As artists, we’re not answering any questions; we’re just putting questions out into the world in a hopeful way. As an artist, you should be optimistic by nature and to see beyond, because we’re creating these things that didn’t exist, and now they do.

Do you think is it more difficult to be an artist at a time when there are so many divides and tensions between different groups of people?

I think that that’s the most important time to be an artist, really. Artists respond to the times. If you’re awake, or woke, and you’re living through the world today, there’s so many issues and tensions. If you’re really angry, you can go to work and figure out ways to put questions back out into the world so that people can pause and think a little bit, like the Visual Tensions project. It’s basically a photograph of police officers and people of color, but that came from me being really angry about what was going on.

Do you ever feel vulnerable by putting so much of yourself in the work and putting that out in the world?

No, but I don’t like going to my openings as much as I used to. I think that it’s like that as you get older and as you get more established. The stakes seem to be different, and they get higher because the expectation is higher to reproduce a certain caliber of work. But that being said, you have to do it. You have to have a certain sense of, “This is good,” or “I feel good about it; I’m going to put it out in the world.” If you didn’t, or if you had these reservations, then what would be the point? You could create work all you want, and you can feel really good about it, and that’s great, and it’s just for yourself. The process has always been for me to create work and put it out in the world. Sometimes it’s really successful, and other times it’s like, eh. It’s really not up to you on how the public takes it, but you have to live with whatever you put out there. Either you’re good with it or not; you just got to do it.

A lot of the subjects in your work are people of color, and it seems like you’re trying to elevate them and put more people of color in the public eye. Do you feel more comfortable doing that now compared to when you were starting out as a photographer?

I think when you’re younger, you’re more inclined to try to do things to get a foot in the world, or you’re trying to get to be known. As you get older in the world, it shapes and molds you. I think that you start to look at things that actually affect you or things that concern you. For me, I’ve morphed more into the way I see the world versus how I fit into it. The way I see the world, in terms of people of color, the politics, the economics, I’m considering all of those things more now than when I was younger, when I thought more about, “How I can make a really cool photograph, and how can I get into this show or work with this client?” The shift for me is less about being a photographer and more about me telling a story and bringing issues up that matter to me. As a black photographer, the things that matter to me are refugees and immigrants from Africa, gentrification, inequality, police brutality. Where do we see ourselves in our communities? How do those things work? I’m not thinking about selling a million photographs. I’m just thinking about putting something out in the world, putting questions out in the world.

Have you ever been surprised by the reaction of subjects when they see their portraits?

I’ve been moved more times than surprised. One time I had taken some photographs of Green Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church and had them up there. This guy was visiting Portland, and he was talking with the pastor. He’s just looking up at the photographs, and he points up to one of my photographs, and he’s like, “That looks like my aunt.” He just started crying because it resonated with him in such a deep way. That was one of the most shocking things. Even though that wasn’t his aunt, at the same time he could take that image and place himself in that moment. With the images of the basketball players [in Voices in Our Midst], when black people see them, they love the intensity of the black skin. They’re like, “I just love the skin.” That’s empowering in a lot of ways, because that was something that we’ve been told not to love for like 200 or 250 years.

How has being an artist-in-residence at Indigo Arts Alliance affected the way you look at your work?

Time and space. It’s created a way where I have time to actually slow down and think, because the outcome isn’t this product that I have to produce at a certain caliber. So, I don’t have those same restrictions that I normally have if I’m on assignment or I have a show coming up. It gives me that space where I can study and read and think and sit and sit with it. The other thing is I’m an African American artist and a black artist, and I have that connection with this black-run organization. I come in here, and I have black people all around me. Nine times out of ten, in any art organization or anything that you do in Maine, it’s just not the same. I’m not saying that I don’t feel comfortable in other spaces, but this is just extra special. I’ve been an artist all my life, and I’ve never had that camaraderie around me. I’ve met other artists of color, but to have this place that you come to—and it’s all hours of color every day for two months—it’s just a different kind of atmosphere. It’s created a safe space to have those difficult conversations that you normally wouldn’t have, or there are things in your head and you’re like, “Oh, did that happen to you? Yeah, it happened to me, too.” It’s created a space and time for me to go off in these directions that maybe I thought about years ago or maybe I haven’t, but I can go into them and see what happens without any expectations of failure or success.

How has Portland changed from when you first moved here?

When I moved to Portland in 1995, it was so undeveloped. It was a bunch of boarded up stores and stuff like that. It was wide open, and it was a bunch of kooky crazy artists, I mean, really talented people living right downtown. Everyone was curious and experimenting and doing stuff. I was like, “Wow, this is a really cool place.” It was this fertile ground for artists to really experiment. I moved from Brooklyn, and I got a studio. That was the first thing I did. I’d never had my own studio, and it was $250 a month, or something crazy like that, for a big old studio. I got to experiment and do my thing. Then me and my wife and two sisters-in-law opened up a gallery called Hinge. We collaborated a lot with MECA. The focus of that was just to show people who usually don’t get to be shown or give an outlet to college kids. We’d go down to New York and buy a bunch of artists’ books to sell. It was before Space Gallery, and we had poetry readings, and we did themed shows like Women’s History Month, Black History Month. We did an exchange with students from Vietnam and MECA. It was just a really cool experience, but you can only do that for so long if you don’t have backing.

Do you think that Portland has lost some of its art scene, or its art vibrancy?

It’s morphed a little bit. I think that from when I first got here, a lot of those artists are doing well, or their careers have developed really nicely. Then there’s some who just fell off the face of the earth. They might be still doing art, but just not here. I think it’s harder for young artists. Before, they had all these alternative galleries. There are still alternative galleries here, but these alternative galleries before were on the street level. June Fitzpatrick had an alternative space right there [on Congress Street]. You go around today and there are no spaces that are just like, “OK, I’m going to show this artist, I really like his work.” It’s more thought out and more precise. Now, the footprint of Cove Street [in East Bayside] is almost as big as all the galleries we lost combined. It’s so huge, but that’s great because they are experimenting. They’re really doing some really cool stuff, and they’re not catering just to sell work. For institutions, we have the ICA at MECA, and we have the Portland Museum of Art, and we have the Maine Jewish Museum. Then you have the Greenhut Galleries downtown, and then there’s a few other galleries. It’s more calculated, and they’re thinking about sellability, not just to show the work. An institution can show whatever, and they’re not selling, but the galleries live and die on sales, and rents are really expensive right now. So, you’ve got to sell a lot of the prints. If I had a show, a solo show at a gallery, literally, for them to make their money, I’d have to sell 15 prints, and selling 15 prints in Portland is really hard. It’s extremely hard. It’s not the same in New York or D.C. or even Boston, where you have that foot traffic from people who come in and they buy prints. But, here, you have to show work between June and August to really make sales, or June and September maybe. I believe it’s still a thriving art scene. I think that it’s just morphed into something different.