Watercolor Painter Abe Goodale Traces His Roots on 700 Acre Island

Inspired by the work of his ancestors, one Maine artist follows his lineage to fill in the gaps of his family’s history.

There are four old chairs in the artist’s studio, lined up against one unpainted wall. They are in various stages of aging; one is too old to sit in, one is sturdy and hale, one is questionable, and one looks almost new. When I take a seat, I don’t realize what I’m placing my bottom on. Later I learn that I’ve chosen my perch well. “That’s my Pop Pop’s chair,” says artist Abe Goodale. “This one, I like to think, was Charles Dana Gibson’s.” I tell him it’s a good thing I didn’t try to use that one. “Yes,” he responds, “I never use it. It’s too precious.”

Goodale is a self-taught painter with a vivid imagination who speaks with intensity and enthusiasm, even about the most mundane of family artifacts, like these four chairs. He is descended from a line of painters and illustrators, the most famous of which was Charles Dana Gibson, the inventor of the “Gibson Girl,” a nineteenth-century phenomenon that defined Gilded Age femininity: the blowsy haired, delicate featured girl was often depicted riding bicycles, playing tennis, and indulging in other athletic leisure activities. One of the most prolific and talented illustrators working at the turn of the century, Gibson had an influence on fashion magazines that can still be seen today. Not only did he document the world of the well-heeled, but he also shaped it with his incisive, witty captions and commentary.

of a cubist sketch.

Goodale’s studio, located on 700 Acre Island off the coast of Lincolnville, isn’t really his. It belongs to “the family,” a rather nebulous group of descendants bound by their shared history of summering on this picturesque island. The other members of their family have allowed Goodale to use the studio, granted him access to their various plots of land, given him permission to walk across their lawns, sketch on their cliffs, paint in their backyards. Throughout my visit to the island, Goodale gently directs our small group (Goodale, me, photographer Nicole Wolf, and Goodale’s two friendly dogs) toward common trails and away from porches. “Family politics,” he says at one point, in explanation. He may belong to this place, but it doesn’t belong to him.

His presence in this historic place is, he says, “an immense privilege,” one that he hopes to honor and repay through his art. Currently Goodale is working on a series of watercolor paintings that are directly inspired by a group of oils by Gibson. “This collection of paintings has never really left the island,” says Goodale of the original canvases. “They were shown once, in New York, in the 1930s and 1940s. But it is work that has never been seen, by an artist who is part of American history.” That alone is a big deal. It’s a major reason why the Maine Arts Commission awarded Goodale a grant in 2019 to develop this project. Goodale is trying to share and promote a piece of local history. He’s trying to tell a story that not enough people have had the chance to hear.

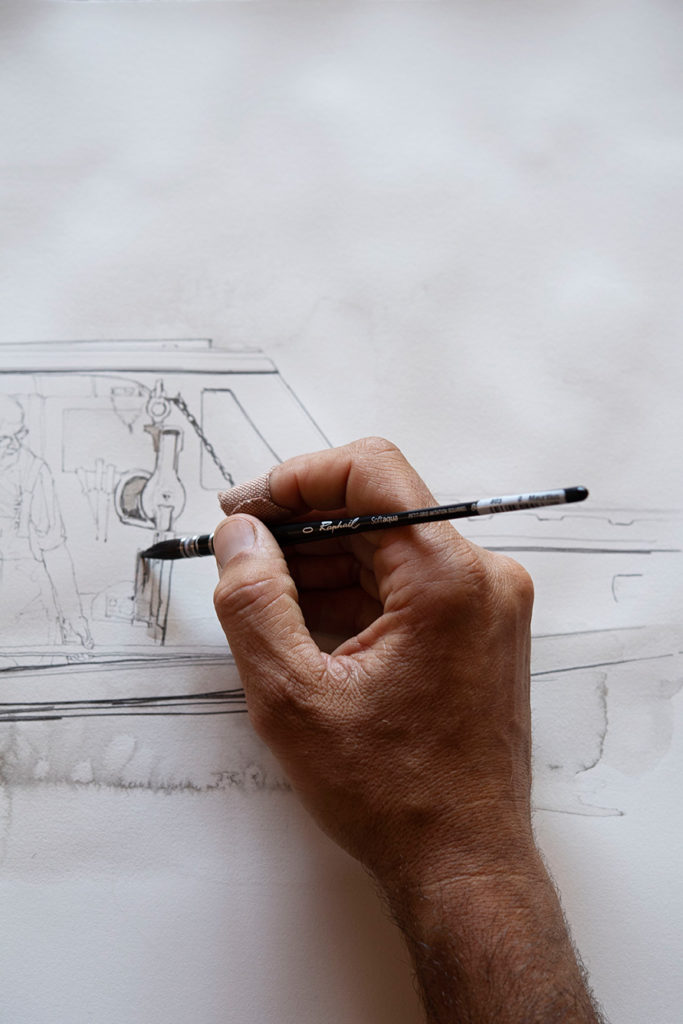

But there are other reasons to be interested in this work in progress. Firstly, he isn’t riding anyone’s coattails. Goodale is a talented painter whose pale watercolors beautifully capture the foggy, vague quality of days at sea. (He makes much of his money through commissioned paintings of boats and harbors, which he depicts with a deft hand and little color.) “Goodale’s portraits of fishermen are true to life, rough and ready men portrayed with cigarettes dangling from their lips or reaching for a line,” wrote art critic Carl Little in a recent issue of Maine Boats, Homes, and Harbors. “There is an authenticity in these portraits that recalls some of Andrew Wyeth’s studies of Maine coast denizens.” Goodale was raised on a sheep farm in Montville, so he’s no stranger to physical labor, and thanks to his father’s connection to the island and the sea, he knows the working waterfront and its inhabitants intimately. He is able to capture Maine in a way that many outsiders couldn’t. He’s close to his subject, and it shows.

But Goodale’s ambitions are larger than simply sharing Gibson’s oils or showing his own watercolors. This is precisely what he plans to do, someday, when the entire project is finished. But Goodale doesn’t just want to add to the historic body of work. He wants to expand upon it, to respond to it, to give it new breath, depth, and texture. He wants to speak across time to his distant, famous ancestor, and in the process, he wants to spark something new. “The most important thing I want to convey with my work, with all my work, is that human-to-human connection,” he says. “It doesn’t matter if something is technically great. It matters if it speaks to someone.” He wants to take people to 700 Acre Island through his art, and to introduce them to the figures that loomed so large in his childhood—his great-great-grandfather Charles Dana Gibson, his uncle Peter Perkins Goodale, and his grandfather Robert Perkins Goodale.

It’s rather lofty stuff, but this is what often happens when you talk to an artist in the middle of a project. You get a vague cloud of an idea, wistful workings, a string of concepts punctuated sharply with examples, the rare specific that helps you see the full picture, like the beak of a nose drawn sharply across an otherwise blandly pretty face. “I’ve asked some of the people who sat for Gibson’s oils to sit for me,” Goodale reveals. Gibson’s grandchildren were a frequent source of inspiration for the painter, and some of them are still alive, still willing to be painted. “I want to go to the same places where he did his landscapes, and create them in my style, showing how the island has changed,” he says. He has also been working on painting the playhouses and chapel, a group of three charming, miniature stone cottages that Gibson built for his grandchildren on a grassy field overlooking the ocean. While it is unknown whether Gibson ever rendered these structures on canvas or in oil, it doesn’t matter. Goodale isn’t trying to recreate every one of the paintings his ancestor did on the island. “In some ways, this is an opportunity for me to fill in the gaps of his story,” he says. “I can represent these things he created, which were such an important part of my childhood, and I can share that with people.” Originally, Goodale had envisioned visiting the locations where Gibson painted and doing his own work in the same space, hanging those two bodies of work, separated by a century, in one show. But now, he says, “I think I want to include the other artists in my family. I want to incorporate text, maybe, to add depth and reference.”

Goodale is still figuring out the details of the show. He’s also grappling with the bigger questions that many of us stumble upon as we age: Where do I fit into the world? What role does my family history play in shaping my life? Where do I fit into my community and how can I be a good citizen? What can I give to the world that will last? For Goodale, the answers are still hazy, which means I trust him to deliver something thoughtful and real. Big questions get shaggy, rangy answers. Big stories aren’t told without digressions. “Right now, a lot of the work I’m doing is just being in quiet. I’m trying to be still and introspective, sitting somewhere and looking,” he explains. He’s not painting constantly or researching. He’s spending a good deal of his time on 700 Acre Island simply being. It’s getting him closer, he believes, to his goal. “In our culture, a lot of us don’t have a sense of roots. We’re floating,” he rightly observes. “It wouldn’t be fair to say that I sit in this studio and feel perfectly at home, but I’m beginning to feel like there’s a lineage. I’m beginning to see it come together.”

Read More:

- The Immortal Life of Holly Meade

- “Beyond the Brick” Brings Maine-Made Art and Music to Life

- Watercolor Painter Abe Goodale Traces His Roots on 700 Acre Island

- Shifting Dynamics Through the Power of Theater

- Shifting Sequences: 2022 Juried Artist Exhibition